The first Veer Bal Diwas underlines the fact that in India, it is stories that make memories. It is these memories that make folk history. This history, in turn, gets ignored by professional historians of a positivistic inclination. Politicians who are sensitive to the multiple undercurrents that flow unseen in every society, manage to use such histories to reach out to people. Reviling these memories as myth-making doesn’t wipe them out or reduce their power.

Over 30 years ago, when Punjab was firmly in the grip of terror and Chandigarh was in perpetual lockdown, the December trimester break at Punjab University introduced me to a unique feature of Punjabi society. While everyone else was celebrating Christmas and planning a warm welcome to the New Year, there were some elders — especially among families that came from Punjab villages neighbouring Chandigarh — who gave up sleeping on beds and abjured common comforts for an entire week. It was just a small period of private grief, not something that any outsider was supposed to notice. On quizzing, one mother said: “It is to recall the sacrifice that the sahibzadas made to save all of us.”

For those unfamiliar with the context, this is the time of the year when temperatures in Punjab are close to freezing and entire weeks go by without the sun. Yet, few talked about what they were undertaking. The elders merely spent a little more time in prayer and once in a while, narrated various stories of the great Gurus, especially about the battle of Chamkaur Sahib and the mental strength shown by the two young sons of Guru Gobind Singh. “Sahibzadas” is how they were addressed.

Brief visits to the then small gurdwara at Fatehgarh Sahib during that period introduced me to a folk memory that was both disturbing and awe-inspiring. Historians had written briefly about them. The state authorities had ignored them. It was mostly people who retold the stories to each other and thus kept them alive. To them, it mattered little that historians had not researched the events around these memories or that those in power had ignored them.

In bare detail, the story is something as follows: Wazir Khan, the Mughal governor, administered territories between the rivers Yamuna and Sutlej. In December 1704, during the reign of Aurangzeb in Delhi, the 10th Guru of the Sikhs and his entourage of a few hundred were attacked as he made his way out of the hill fastness that is today known as Anandpur Sahib. In the melee that followed, known as the Battle of Chamkaur Sahib, the two elder sons of Guru Gobind Singh were killed and the two younger ones aged 6 and 9 years, got separated. The Guru himself escaped, helped by two Pathans, Ghani Khan and Nabi Khan, and eventually took shelter in the house of a local Muslim chief.

The younger boys, along with their 81-year-old grandmother, Mata Gujri, took shelter with a servant who betrayed them to the Mughals. They were now kept in a bare draughty room in the fort at Sirhind while the Mughals took their time to decide about their future. Three weeks later, Wazir Khan made them an offer. Convert to Islam, or else…

He offered to spare their lives if they were to accept Islam.

The boys refused.

Wazir Khan ordered that they be bricked in, alive. That date is etched into the memories of Punjab. It was what is now known as the 27th of December, 1704.

Mata Gujri died of shock.

Over the next few years, Aurangzeb passed away. His empire quickly crumbled and Banda Bairagi took over much of eastern Punjab. In the summer of 1710, Banda killed Wazir Khan at the Battle of Chappar Chiri, a small village on the outskirts of what is now known as Chandigarh and took control over the territories of Sirhind.

The chamber where the Sahibzadas were bricked in, the Bhora Sahib, became a place of pilgrimage for everyone. Eventually, a gurdwara came up around it. Nowadays people assemble each year in the last week of December to remember the suffering and sacrifice of the family that held up the dignity of their religion and refused to succumb to an oppressive Islam. The gathering is not called a “Jor mela”, literally a coming-together-fair. Rather, it is called “Jor Mel”, the occasion for everyone to put their heads together to think about the sacrifices made by the sahibzadas and the gurus and how to lead a more ethical life.

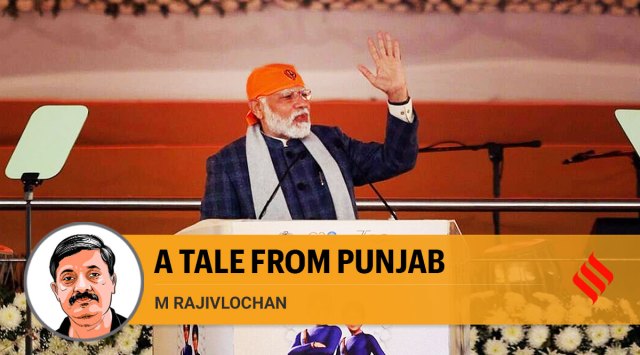

As with all living traditions, this tale too is considerably undocumented. Perhaps for that reason alone, the complex messages underlying it remain alive, especially the need to retain mental strength in the face of adversity and a strong ethical commitment to one’s beliefs. Embedding it in the national calendar of India in the form of Veer Bal Diwas makes it accessible to the entire country. The prime minister, of course, hopes that this would also carry to the young a message about commitment to the motherland, to one’s beliefs, and ethical living. After all, the young do need to have hope and develop the mental strength to not give in to adversity. It would be too simplistic to imagine that embedding a memory from Punjab into the national consciousness will result in Punjabi votes for the BJP in the next general elections.

The writer is professor of History at Panjab University