A rail line to Jammu & Kashmir is more than just a tale of tracks, bridges and tunnels. The saga to connect one of the country’s most picturesque regions by rail link with the rest of India spans over a century. That saga is expected to culminate later this month, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurates the remaining 63-km Katra-Sangaldan section of the 272-km Kashmir line, also called Udhampur-Srinagar-Baramulla Rail Link (USBRL).

The importance of connecting Jammu & Kashmir with the rest of India by rail was recognised back in the 1890s. As part of his Punjab-Kashmir Project, in 1889, Raoul De Bourbel, a Major-General in the Royal Engineers of the British army, conducted the first survey for a rail line from Jammu to Akhnoor, located on the banks of the Chenab. Eight years on, the state would get its first rail line, from Jammu to Sialkot (in present-day Pakistan). However, a rail line to the Valley was still a distant dream.

In 1898, Maharaja Pratap Singh of Jammu & Kashmir proposed the idea of a rail link to the Valley. The British administration saw strategic merit in his suggestion despite the challenges. The Maharaja commissioned a detailed survey in 1902, which threw up four potential rail pathways.

British engineers proposed a rail link along the Jhelum, connecting Srinagar to Rawalpindi. However, this proposal was rejected since Jammu residents travelled to Srinagar in Kashmir via the Mughal Road, which connects Poonch and Rajouri to Srinagar in the Kashmir Valley.

The other routes suggested by the surveyors included the Banihal route from Jammu (which involved crossing the Pir Panjal range via the Banihal Pass), the Poonch route along Jhelum valley; the Pajar Route (which would start from Rawalpindi, located in present-day Pakistan);and the Abbottabad route (in present-day Pakistan, which would start from Kalako Serai and pass through Hazara in the Upper Jhelum Valley, also called the Kashmir Valley). Despite these suggestions, the ambitious project did not materialise.

Buoyed by the survey results, the colonial government in 1905 once again proposed a rail link between Rawalpindi and Srinagar. However, Maharaja Pratap Singh approved a rail line between Jammu and Srinagar via Reasi through the Mughal Road.

According to Tracks of Triumph: Connecting Kashmir, written by Himanshu S. Upadhyay and published by Northern Railway, this audacious line — from Jammu and Srinagar via Reasi — would have involved a 2-foot or 2.6-foot gauge railway (distance between the inner sides of two rails of a track) “climbing” all the way to the Mughal Road.

“It (the track) was set to pass over the Pir Panjal range near Banihal at a much higher elevation of 3,353 meters as compared to the present day Pir Panjal Railway Tunnel, which is at 1,760 meters. As planned, it would have been electric-powered and would have used the mountain streams to generate the required electricity. If built, the rail line would have been spectacular, but the narrow gauge and high-altitude pass would mean it was not all-weather and also constrained to low speed and capacity, similar to Darjeeling Himalayan Railway,” states the book.

Besides the many engineering and operational challenges in building a rail line at such a high altitude, the estimated cost was far too enormous for the Maharaja and the British. A glimmer of hope soon appeared, says the book, in the form of the discovery of coal in Ladda area, nearly 50 km from Tikri in Jammu’s Udhampur. At first, officials thought that this would solve the issue of the project’s energy requirements, but the logistical challenges of mining coal from the difficult terrain rendered the “solution” as impractical for over two decades.

The Kashmir rail link file would resurface in 1928, based on recommendations by R R Simpson, a mining specialist with the Geological Survey of India (GSI), and C S Middlemis, a superintendent with GSI, in their 1904 Mineral Survey Report. Though the matter was discussed between Maharaja Hari Singh of Jammu & Kashmir and the North-Western Railway administration, both the proposal and the plans for a survey were eventually dropped.

In 1937, Karnail Singh, who had retired as the Railway Board chairperson, conducted a survey from Jammu to Akhnoor. Barring the construction of a 30-km line between Jammu and Sialkot (in present-day Pakistan), the dream for a Kashmir rail link remained unfulfilled.

A series of events in the early 20th century would derail the Kashmir rail project for a while. Besides World Wars I and II, which consumed the resources and attention of the colonial government, the Partition sounded the death knell for the Jammu-Sialkot rail link.

Despite these setbacks, the Indian Railways kept pushing its boundaries to reach the Valley. The very first effort was made after Independence, when the Jalandhar-Mukerian line in Punjab was extended to Pathankot and made operational in 1952. Two surveys by Indian Railways engineers in 1961 and 1962 did not result in major discoveries.

In 1964, prompted by the Defence Ministry, a potential rail link to Udhampur was explored. “The proposed route ran behind the first row of hills, following the Sundrikot Dhar and Dhar-Udhampur Road, covering a distance of 53 miles (over 85 km) from Kathua to Udhampur…However, the feasibility study revealed that despite being shorter by about 40 miles (over 64 km) compared to the road, the rail link was not justified on commercial ground,” states a chapter in Upadhyay’s book.

By 1966, marking an incremental yet largely symbolic progress, the railhead (the point at which a railway ends) advanced from Pathankot to Punjab’s Madhopur and then to Kathua. The significant breakthrough came in 1969 — when a project to extend the rail line beyond Kathua to Jammu was initiated.

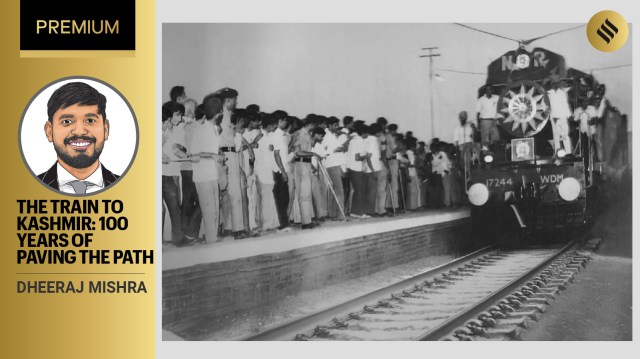

In 1971, the final survey for a metre-gauge electrified line from Qazigund to Baramulla was carried out. On October 2, 1972, the Kathua-Jammu section was opened for goods traffic, marking a major milestone. Two months later, on December 2, the Srinagar Express, now called the Jhelum Express, made its first run from Pathankot to Jammu. According to the book, the construction of this line continued unabated despite the 1971 India-Pakistan war, making it one of the few examples in the world of critical infrastructure projects persisting even during wartime.

After this, a preliminary survey in 1973-74 proposed a broad-gauge through the Shivaliks at an estimated cost of Rs 50.3 crore and a projected completion time of 10 years. Sanctioned in 1981-82, increased funding in 1994-95 led to its construction gaining momentum. In 1983, then Prime Minister Indira Gandhi inaugurated the construction of a line from Jammu Tawi to Udhampur, with the final location engineering survey via Manwal carried out in the same year.

In 1994, the cost for the construction of the new broad-gauge between Udhampur and Srinagar was included in the Budget. Its scope was later extended to Baramulla. In 1995, the Udhampur-Katra rail link was sanctioned, followed by the Katra-Qazigund and the Qazigund-Baramulla links in 1999. The line between Jammu and Udhampur was finally opened in 2005.

In 2002, then Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee declared the Kashmir Rail Link as a “national project” and termed it as an ambitious vision to connect the Kashmir Valley with the country’s rail network. On October 11, 2008, a 68-km section from Anantnag to Mazhom was opened by then Prime Minister Manmohan Singh. Two sections were inaugurated in 2009 — a 32-km section from Mazhom to Baramulla and a 18-km section from Qazigund to Anantnag — followed by the 18-km Qazigund-Banihal section in 2013. In 2014, PM Modi inaugurated the 25-km Udhampur-Katra stretch. The last stretch of the USBRL — the 48-km Sangaldan-Banihal section — was commissioned in February 2024.

While trains are operational between the Jammu and Kashmir sections separately, the stretch that will be inaugurated by PM Modi will not only connect the Valley with the rest of the country, it will also reduce the travel time between Jammu and Srinagar, and make disruptions in travel by road due to uncertainties of climate a thing of the past.

The writer is Principal Correspondent, The Indian Express