Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer has unleashed myriad conversations about atomic bombs. For some, it is an affirmation of the Bhagavad Gita’s timelessness, since the father of the atomic bomb used to read it. Many on social media circulated a picture of Jawaharlal Nehru with Oppenheimer. “Now I Am Become Death, the Destroyer of Worlds,” is being quoted left, right and centre.

This conversation nevertheless bypasses an important point — India’s contribution to strongly declaring the first use of nuclear weapons illegal in all circumstances. It might surprise readers that the International Court of Justice (ICJ), the principal judicial organ of the United Nations, when asked in 1996 in Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons whether the use of nuclear weapons is illegal, refrained from declaring it so.

Judge Mohamed Shahabuddeen and Judge Christopher Weeramantry dissented from the majority, quoting verses from the Bhagavad Gita. Shahabuddeen noted that “Oppenheimer could read the verse in the original Sanskrit of the Bhagavad-Gita.” The Sri Lankan jurist Weeramantry’s famous dissent noted, “that the use or threat of use of nuclear weapons is illegal in any circumstances whatsoever… It endangers the human environment in a manner which threatens the entirety of life on the planet.”

The “Declaration of Public Conscience” campaign in Japan garnered 17,57,757 signatures in favour of banning the use of atomic weapons by international law.

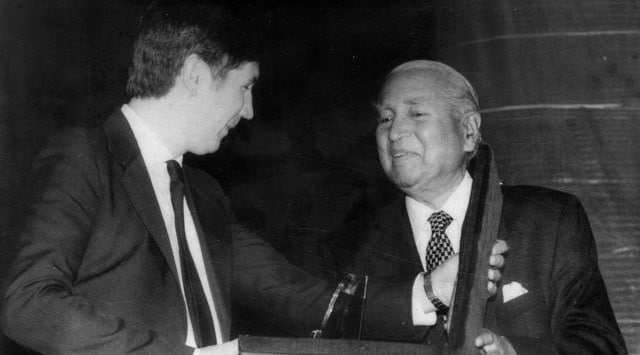

Incidentally, Justice Weeramanty had been elected to the ICJ to fill in the vacancy created by the untimely death of Judge Nagendra Singh in 1988 (punctuated only by an interim stint of Supreme Court Judge R S Pathak). Singh joined the Court in 1973. Born in the royal house of the Dungarpur estate, Rajasthan, Singh rose through the ranks of Indian civil service, to become the secretary to India’s acting President and Chief Justice, Mohammad Hidayatullah in 1972. In his dissent, Weeramantry infused the case law of the world court with Judge Singh’s juristic opinion on atomic weapons.

Singh made major contributions at the world stage that are not well known. He was one of the world’s leading jurists on the legality of the use of nuclear weapons. In his 1959 book Nuclear Weapons and International Law, Singh argued that to “resort to such weapons is not only incompatible with the laws of war but irreconcilable with international law itself”. Singh explained his opinion in purely legal terms. When the substantive aspects of the laws of war were considered, he argued that the use of nuclear weapons on any scale would involve a refusal to distinguish combatants and non-combatants as well as military targets. This would effectively violate the legal obligations of the laws of war. For Oxford professor Ian Brownlie, Nagendra Singh and M C Setalvad, India’s first Attorney General, presented “more valid” and “tenaciously held positions” on the matter than any other jurist of the time.

Fortuitously, the ICJ was faced with its first case on the legality of the use of nuclear weapons in the very year Singh was elected to the Court. In May 1973, Australia and New Zealand each instituted proceedings against France at the world court concerning tests of nuclear weapons, which the latter was carrying out in the South Pacific region. The ICJ indicated provisional measures to the effect that pending a decision by the Court, France should avoid nuclear tests. The Court ultimately found no dispute to be settled in law since France subsequently announced its intention to suspend any further nuclear tests after 1974.

Judge Singh thus missed the opportunity to present his views on the legality of the use of nuclear weapons. Notably, India conducted its first nuclear test within a week of the ICJ ruling in the Australia v France case — in Nagendra Singh’s home state of Rajasthan.

Be that as it may, it was not the possession of nuclear weapons that Singh had argued was illegal but their use. This was the Bhagavad Gita’s central message as Judge Weeramantry would note at the ICJ in 1996. Based on Singh’s arguments, Princeton Professor Richard Falk argued for the “intrinsic illegality” of the use of nuclear weapons. Falk drew sharp reactions from US academia and most leading American law journals refused to publish his co-authored paper. The Indian Journal of International Law, at the time the subject’s leading journal, published the paper. Judge Nagendra Singh’s discourse on the use of nuclear weapons is worth remembering today.

The writer is professor of law, BML Munjal University