In the 1850s, Muktabai Salve, a young Dalit woman, wrote a strongly worded, angry critique of Brahminism and the upper caste monopoly of knowledge. A student at a school for girls set up by Savitribai Phule and Jyotiba Phule, Muktabai spoke with confidence and without fear. She was 14. Savitribai herself had been a mere 17 or 18 when she and her husband set up the first girls’ school in Pune. Three more schools followed in as many years. With the help of friends Usman Sheikh and his sister Fatima, probably close to Savitribai in age, they went on to do much more. Tarabai Shinde, another Maharashtrian, and a woman who taught at Savitribai’s school, was 32 when she wrote a searing critique of patriarchy, Stree Purush Tulana, one of the first feminist documents on record in India.

Things were not easy for these young women in their lifetimes. History tells us that Savitribai faced much opposition and criticism as her schools included women of all castes and also widows, otherwise socially ostracised. The story goes that when she left her home to go to teach, people on the streets would throw rubbish at her — the modern-day version would be online abuse — but that she, well aware how to deal with this, would carry a spare sari with her, into which she would change once in the school, and be clean and fresh for her students. Tarabai Shinde, too, faced abuse and vile criticism for daring to speak out against patriarchy, and she, sadly, never wrote anything again.

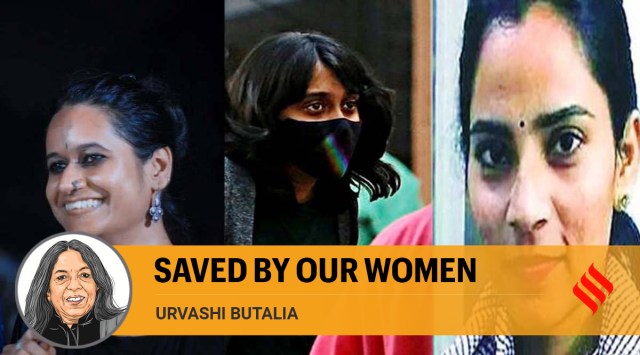

Today, as I watch the joyous release (albeit on bail) of activists Devangana Kalita and Natasha Narwal from Tihar Jail after a year of being held on what seem to be flimsy and trumped up charges, I am reminded of the rich — and barely documented — legacies of our foremothers. Were they to look down on earth from wherever they are, Muktabai, Savitribai, Fatima Sheikh, Tarabai would see an amazing and yet not unfamiliar picture.

In Burgum village in Dantewada, they’d see a tribal woman in her late twenties, walking from village to village, painstakingly collecting information about people unfairly imprisoned, proof of no wrongdoing, that may help to get them released. Hidme Markam works with the Jail Bandi Rihai Manch, and she manages to collect information about a hundred of the 6,000 incarcerated tribals when she is arrested and jailed. It would appear that the powers that be fear their lie will be exposed if she completes her task successfully.

In Bangalore, they might see Amulya Leona Noronha, a 19-year-old student, arrested on sedition charges for shouting “Pakistan Zindabad” (reportedly followed by “Hindustan Zindabad”) and thrown into jail.

Then, their gaze may find Disha Ravi, early twenties, fighting to draw attention to the dangers of climate change, arrested for putting two edits into a google doc containing a toolkit of sorts for environmental activists. The charges against her include sedition, and waging economic, social, cultural and regional war against India.

In Haryana they’ll find Nodeep Kaur, mid-twenties, journalist and activist, who works with the Mazdoor Adhikar Sangathan, arrested once again on what seem to be trumped up charges, allegedly because the corporates fear the battle she’s part of, for workers’ rights. She isn’t fooled by the many FIRs that have been registered against her. “It’s because we are Dalits,” she says, “they don’t want us to assert our rights.”

Inside Tihar jail (now released on bail) they would’ve found Natasha and Devangana, in their thirties, following the dictum — if you don’t have access to the outside, try to change what’s inside — and arguing for the human rights of prisoners, building libraries for children and women.

Then their collective gaze may come to rest in Araria in Bihar where two young people, Tanmay, a trans man, and Kalyani, his colleague, have been thrown in jail, reportedly for having the gall to help a rape survivor understand the statement she is being asked to sign. In jail, they campaign for the rights of prisoners, and better jail conditions. Out on bail, they continue this fight and draw attention to other things such as the need for toilets for trans people in prisons.

Across the world, one of the anxieties of the early feminists has been whether or not there will be a new, young generation to continue the struggle. In India, it’s clear there’s no cause for worry. This handful of activists (and I have named only women, barring Tanmay) from across class and caste and gender are joined by thousands of others, too numerous to mention here.

There’s significance also in the issues they have taken up: Tribal rights, workers’ rights, Dalit rights, women’s rights, student rights, climate change, nationalism and borders, farmers’ rights, citizenship rights and so much more.

Not all of them will see themselves as feminist, but all will recognise the inseparability of women’s rights from the issues they choose to prioritise.

Not everyone in this list is elite, not everyone urban or middle class, not everyone savarna. What they have in common, though, is the courage of their convictions, the determination to fight, a mature political understanding, and the resilience of youth.

For those who see themselves as feminist, even as they own their history, they do not hesitate to raise hard, difficult questions about power and its abuse even within feminist movements.

Small wonder, then, that state authority so fears them — youth unbridled, youth given its head, is a dangerous and worrying phenomenon for those who seek to control. For every policeman who raises a stick to the brave young feminists, the anxiety he is dealing with is real. For, in them, he sees the paths his daughters will surely take as they begin to assert themselves and assume control and he begins to lose it.

It’s time we took our young feminists seriously, and started listening to them.

This column first appeared in the print edition on June 25, 2021 under the title ‘Saved by our women’. The writer is director, Zubaan publishers.