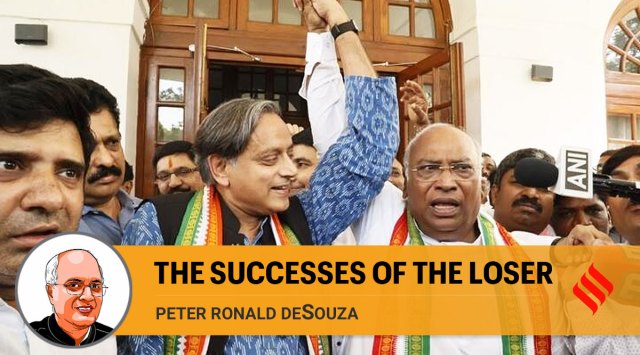

Kharge won, he got 84 per cent of the vote. Tharoor lost, as expected. His vote share was not insignificant. I believe that this election for the president of the Congress party is a defining moment in the history of the party system in India, or even perhaps of Indian democracy.

Reading the tea leaves today is to distinguish between the probable and the possible. Causal explanation is required to make sense of the data, as many commentators have mechanically done when noting the challenges before Kharge, while prophecy is required to rearrange the data and read it imaginatively through the lens of history. Prophecy’s value lies in its acknowledgment of the intangibles of human nature thereby producing a narrative that combines aspiration, realism, and fact.

The election of the Congress president, after about 25 years, with no member of the Gandhi family as a candidate, is such a fluid moment in Indian history. Agency is at play. Whether it will redefine the future of the party, and of politics in India, will depend on how the various actors of this moment — Kharge, Tharoor, Gandhis, party grandees, young turks, new recruits who have joined after the Bharat Jodo yatra, allies, especially NCP, RJD, TMC, DMK, Shiv Sena (T), ex-Congress men and women, and of course the NDA — respond to this fluidity. Such a moment of openness is ephemeral and requires the many agents to make a choice. Will they be daring or timid, change the system or submit to it?

Tharoor’s role has just begun. He lost. But he also won. While most commentators have focused on Kharge’s victory, his years of public service, closeness to the Gandhis, fierce commitment to Congress ideology, caste identity, challenges before the party, formidable opposition of the BJP etc, I shall comment only on the successes of the loser.

With his posh accent, Tharoor’s campaign began at the heart of the British establishment, the Oxford Union debate. He charged Britain’s favourite Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, with a crime against humanity for diverting food from Indian peasants leading to the tragic famine in Bengal. He criticised British colonialism for the damage it caused Indian industry, asked for the Kohinoor back, and demanded reparations for the harms done. Tharoor won that debate. The embarrassed and overwhelmed Britishers in attendance politely applauded. His performance charmed nationalists of every hue in India, including many Sanghis. His speech was a brilliant illustration of the Nehruvian idea of inclusive nationalism very different from the whining nationalism of the Savarkarites. And not a whimper from the NDA.

His second success is his insistence on forcing an election for the Congress president against the many who wanted unanimity. By forcing the election, he silenced, or maybe weakened, the voices that called it a sham, a front for the Gandhis. He thereby opened space for genuine party reform. Whether it will be taken up depends on the various actors mentioned earlier. Will they seize the moment? Four sets of actors are important to turn this political space into an opportunity for a new party politics. The first are the 23 signatories, the party grandees. The second are the former Congressmen who preside over their own parties. The third are the state-level parties who are the Congress’ allies. And the fourth are the assortment of civil society organisations who, having joined the Bharat jodo yatra, still adopt a holier than thou stance of not wanting to be soiled by Congress politics.

Led by Kharge, provoked by Tharoor, enthused by the two-month media coverage the election produced, the Congress is back. The more open-minded among this set of actors are being challenged to recognise the historic opportunity and accept their responsibility. Tharoor’s candidature created this space for choice. At this moment it may not be farfetched to suggest that maybe, just maybe, the Gandhi family may wish to withdraw from the centre of party life, fade into history, and do so without being accused of abandoning the ship. It may be the pivotal moment of restoring the practice of genuine competitive succession. Tharoor prepared the ground for collective party building, for new ideas to be tried without fear of offending the Gandhis, for a post-Gandhi Congress. It is today a real possibility.

Although the next point reads as a continuation of the second, it, in fact, has independent status. Tharoor’s third success is the removal of the fear of the family. Criticism of policies, especially those prepared by the leadership, can now move from behind the darbar curtain to the darbar hall itself. This will be a huge advance for the Congress party. It will open up the feedback loop blocked by years of sycophancy. A feedback loop is necessary for any successful political organisation. The BJP, in contrast, has diminished its own feedback loop, thereby setting the stage for its eventual decline. Will the Kharge Congress grasp this opportunity, using digital technology and PCC platforms?

The fourth success is the respect for ideas that Tharoor’s candidature has brought back into public discourse in opposition to the current climate of anti-intellectualism. He has done it in style. He has made ideas vibrant and fun. Tharoorisms proliferate on social media. Through his self-deprecatory humour, a style in short supply during this NDA regime, he has restored an important element of a healthy democratic politics. Having vanquished the colonialists, Tharoor must continue to flail the rakshasas of Indian politics who mock his Lutyens colleagues and his Khan Market friends.

His final success lies in effectively nudging the Indian polity towards the Kerala model of politics for the nation. We are too diverse a society to have a two-party national political system. We must accept that we are a federal party system that must be nudged towards supporting a two-front competitive party system. This must be encouraged through a relentless campaign in all media. For him this will be easy. Social media loves him. He still has work to do.

Peter Ronald deSouza is the DD Kosambi Visiting Professor at Goa University. He has recently co-edited the book Companion to Indian Democracy: Resilience, Fragility and Ambivalence, Routledge, 2022.

Views are personal