Aankhon ko visa nahi lagta, sapno ki sarhad hoti nahi/ Band aankhon se roz sarhad paar chala jata hun milne/ Mehdi Hassan se

(The eyes don’t need a visa, dreams don’t come with borders/ With closed eyes, every day, I go across the border/ to meet Mehdi Hassan)

Gulzar’s tender lines capture what the cold logistics of Partition could not – that the threads that bind India and Pakistan go beyond their traumatic past and fractured present. That the shared heritage also embraces all that could be a salve on their wounds — language and movies, music and food, poetry and sports.

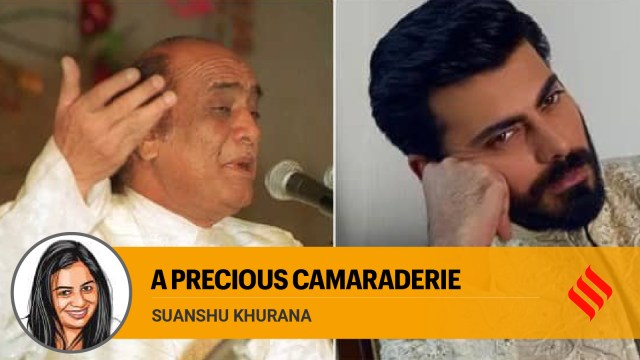

Despite the Line of Control cutting through the hearts of the two nations, no one could ever divide one’s affections for Hassan’s Ranjish hi sahi or not be touched by the clarity of Lata Mangeshkar’s voice. The stubborn simplicity of Ghulam Ali’s Hungama hai kyun barpa demanded quiet surrender while few could resist the emotive sway of Calcutta-born Farida Khanum’s Aaj jaane ki zid na karo.

In the early 2000s, before the Fawad Khan fever swept through India, one’s affections were also for Junoon (the Pakistani band that even performed in Jammu and Kashmir), Ali Haider’s 90s farewell favourite Puraani jeans and, of course, the fabulous Jal, the pop band from Lahore.

If 26/11 stalled these exchanges, the situation took a turn for the worse in 2015 when Shiv Sena protested against Ghulam Ali’s tribute concert for ghazal singer Jagjit Singh in Mumbai and forced its cancellation. The misfortune was not his — it was that of music lovers from either side of the border. But after 2016’s Uri attack, there was a blanket ban by the Indian Motion Pictures Producers Association and the Federation of Western India Cine Employees on Pakistani artistes working in the Indian film industry. Pulwama attacks in 2019 only reinforced it.

The internet may have shrunk our worlds, making it possible for us to catch a rerun of a Fawad Khan serial or a song by Rahat Fateh Ali Khan. In increasingly polarised times, it could even take the edge off to evoke a sense of respect and awe. But, with political daggers drawn, what it could not do was to create a space for collaboration. And so we waited, the citizens of both countries, occasionally revelling in the glory that was Ali Sethi and Shae Gill’s Pasoori, watching the former do Zoom chats with Indian artistes and wondering if Dubai was where one would need to go to listen to collaborations between Indian and Pakistani artistes. But that option was never going to be feasible in the long run.

Last week, the Bombay High Court quashed a plea to ban Indian companies, citizens and associations from working with Pakistani artistes – including actors, singers, musicians, lyricists, and technicians – in India. The plea, filed by Faaiz Anwar Qureshi, a cine worker, was rejected because, the court observed, that “in order to be patriotic one need not be inimical to those from abroad especially, from the neighbouring country” and that art, music, sports, culture, dance “rise above nationalities, cultures and nations and truly bring about peace, tranquillity, unity and harmony in the nation and between nations.”

The court’s observation was a salaam to the basic tenets of art, its capacity to evoke a sense of community, solidarity and self-awareness, especially when nothing else manages to get through people’s hearts. The camaraderie between the Indian and Pakistani cricket teams – both men’s and women’s – had already given us a sense of it. It’s impossible to not have one’s heart full after looking at a selfie in which members of the Indian cricket team are trying to be in one frame with Pakistani captain Bismah Maroof’s baby or Shaheen Shah Afridi handing a present to Jasprit Bumrah for his newborn son.

These exchanges work as reminders of people’s capacity to appreciate not just each other’s brilliance but also their ability to rise above differences to find ways to collaborate.

The truth of the reach of arts was once explained by Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan, whose village, Kasur, fell in Pakistan but who later decided to stay in India. “If one child in every home had been taught music, India would never have been partitioned.”

suanshu.khurana@expressindia.com