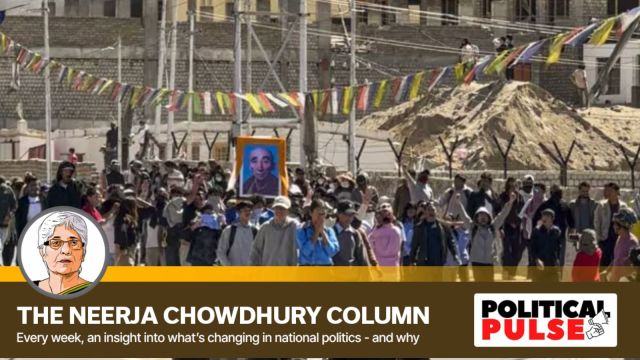

The day Sonam Wangchuk was arrested, a young friend from Kohima called me, deeply concerned about the developments in Ladakh. He and his friends had heard Wangchuk speak in Nagaland and said the climate activist had repeatedly emphasised that “we have to fight for our rights and dreams only through non-violence”. According to Wangchuk, it is the only way to convince those in “heartland India” who need convincing.

Last week’s protests by young people in Leh that suddenly turned violent, leaving four people dead, are likely to have a ripple effect beyond the Union Territory. It has already led to a halt in the ongoing talks between the Centre and the Apex Body, Leh (ABL), which represents Buddhist-majority Leh, and the Muslim-dominant Kargil Democratic Alliance (KDA) over the demands of statehood and Sixth Schedule status for Ladakh. At the root cause of the crisis is a lack of jobs for locals and the inability of the people of the region to resolve them on their own, as they allege that their local bodies are “virtually defunct”.

Ladakh’s Lieutenant-Governor Kavinder Gupta, however, has held a “foreign hand” responsible for the protests, claiming that the whole of Ladakh would have burnt had the police not opened fire on the protesters. Over the years, governments have tended to blame the “foreign hand” amid popular protests (Indira Gandhi was a master at it). But people tend to view such rhetoric with scepticism. And yet, it is also true that today, in the fast-changing, post-Trump global order, India has to be extra vigilant about forces that may want to use popular angst and disaffection to foment trouble.

That is all the more reason why the internal situation needs to be calmer and more stable. Surely, protests and demands for statehood or Sixth Schedule status, which four states in the Northeast also enjoy, cannot be labelled anti-national. Such charges only go to increase contention and not de-escalate the situation. The question remains: why was there such a heavy-handed response in a sensitive border region, when this ran the risk of becoming counter-productive?

Protests are an inalienable part of any democratic polity. But they also provide the best feedback to any government about what is bothering people so that it can take timely steps to address their concerns. Just as it is the role of the Opposition to hold up a vision for the country, it is the government’s job to govern it and manage things before they get out of hand. And when protests take place, it is necessary to talk, and talk, and talk, if required. Unfortunately, people are beginning to see the State as an entity that “legitimatises violence”, as a villager in Bhiwani, Haryana, put it after the recent murder of a woman schoolteacher that sparked widespread protests.

The BJP that was in the Opposition for half a century should have understood, more than most, the dynamics of protests and the need to navigate, negotiate, and, if nothing else, ensure a conversation with those raising their voices. In power for 11 years, the ruling party seems to have slipped up here.

In the past few weeks, protests led mainly by the youth have occurred in different parts of the country.

Less than two weeks ago, hundreds of young people came out on the streets of Panjim in Goa to protest against the killing of a social activist. A gang suspected of enjoying political patronage was allegedly behind the murder that occurred in broad daylight on one of the busiest streets and despite the presence of CCTV cameras. This stunned Goans and such was the public outrage that, according to reports, the police shut the gates of their headquarters and the BJP its office entrance.

Uttarakhand has also witnessed widespread protests following paper leaks in the Uttarakhand Subordinate Services Selection Commission. Paper leaks are becoming a live issue in several states, with students who toil for years getting upstaged.

The tragic stampede in Tamil Nadu at actor-turned-politician Vijay’s rally was not, technically speaking, a protest of the kind under discussion here. And yet it was an extension of protest politics, as a large number of youth who turned up at the rally are now tired of old politics and in search of new faces.

Given the resilience of our democracy, however flawed it may be, protesters have in the past become stakeholders in the country’s evolving and devolving politics. The Aam Aadmi Party is a recent example. It was born as an anti-corruption movement and is a national party today, in power in Punjab. In the 1980s, the Asom Gana Parishad ruled Assam, having started as a youth-led movement against illegal immigration.

Protest movements have often refashioned the country’s politics. When these movements were handled with care and sensitivity, they yielded results, as with the formation of Jharkhand, Chhattisgarh, and Uttarakhand. These smaller states were created smoothly and without violence or rancour, no small achievement.

But in the absence of a dialogue, the outcome can be very different. The youth-led Nav Nirman Andolan in 1973 in Gujarat devoured the government of Chimanbhai Patel, escalated the following year into the Bihar movement helmed by Jayaprakash Narayan, and ultimately led to the imposition of the Emergency in 1975. Two years later, it led to Indira Gandhi’s ouster from power and the formation of the first non-Congress government at the Centre.

We cannot forget that we are a young nation with 65% of our population below the age of 35. The youth are aspirational and big dreamers, given their exposure to the world of the Internet and digital media, but without the skillsets and opportunities to translate their dreams into reality. Thus, we could possibly see more, rather than fewer, protests in the coming days, given the increasing problem of livelihoods and the rising frustrations that come with joblessness and corruption.

Like in Nepal, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka, this could be fuelled by social media, but unlike our neighbouring countries, India is too large, diverse, and institutionally stable. Yet, as Ladakh shows, challenges remain and meeting them will call for restraint and wisdom from both the government and the Opposition.

(Neerja Chowdhury, Contributing Editor, The Indian Express, has covered the last 11 Lok Sabha elections. She is the author of How Prime Ministers Decide.)