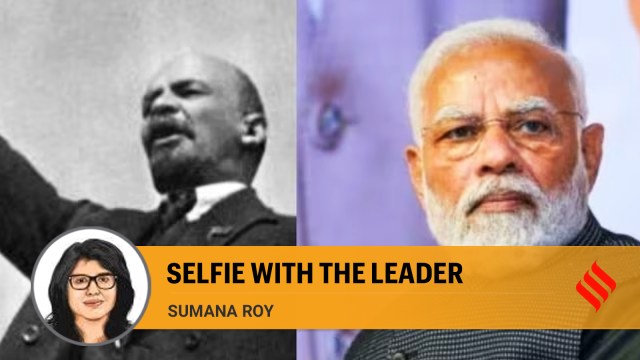

“There was baby Lenin, looking like a cherub in his blond curls. Then Lenin in his twenties and thirties, bald and uptight, with that meaningless expression on his face which could be mistaken for anything, preferably a sense of purpose. This face in some way haunts every Russian and suggests some sort of standard for human appearance because it is utterly lacking in character.” This is Joseph Brodsky in his essay ‘Less than One’, trying to understand how the “militarisation of his childhood” and his encounter with Lenin’s photos everywhere, in offices and homes, in all imaginable and unimaginable locations, led him to see the world like he did.

I was reminded of Brodsky’s essay when I came across a recent letter — now retracted after protests from student and teacher bodies — from the University Grants Commission to all universities and colleges in India: “Let us celebrate and disseminate the incredible strides made by our country by establishing a ‘Selfie Point’ within your institution. The aim of ‘Selfie Point’ is to create awareness among the youth about India’s achievements in various fields, particularly the new initiatives under the NEP 2020”. A Google Drive link led to seven suggested “designs” for “Selfie Points” that the heads of institutions were asked to follow. The first of these was “Ek Bharat Shreshtha Bharat — there was Mohandas Gandhi on one side and Narendra Modi on the other, and, in between them, a girl with a phone taking a selfie. There’s the PM again, this time alone, in the next suggested design: “Smart India Hackathon”. In “IKS: Indian Knowledge Systems”, an Amar Chitra Katha-style Brahmin-looking scholar sat with a manuscript in front of him, Modi standing at the other end, looking at the camera as always. The Indian student must find a place between the two as if they are bookends of Indian history.

“I think that coming to ignore those pictures was my first lesson in switching off, my first attempt at estrangement… Anything that bore a suggestion of repetitiveness became compromised and subject to removal… In a way, I am grateful to Lenin. Whatever there was in plenitude I immediately regarded as some sort of propaganda,” writes Brodsky, “In a centralised state, all rooms look alike…” Offices and schools and classrooms looked like replicas of interrogation chambers. The décor was maddening; the same portraits – Lenin, Stalin, members of the Politburo, Maxim Gorky. The UGC selfie points, with their infinite repetitions of Narendra Modi, were, quite visibly, meant to be an optic of “propaganda” – and so, the “offices and schools and classrooms” must all “look alike”? After all, it is the nature of administrators to be narcissistic, to want to clone themselves as their nation.

I am writing this on the Vande Bharat Express, photos of Modi inaugurating the train running on the monitor behind me. Lenin’s face hung from the walls, surveillant; Modi stands beside the imagined student, indifferent. The resistance to Lenin’s face produced Joseph Brodsky, a school dropout who went on to win the Nobel Prize. What will the resistance to Narendra Modi’s face produce?

Roy, a poet and writer, is associate professor of creative writing, Ashoka University. Views are personal