Written by Ramzan Shaikh

Recently, the Ministry of Tribal Affairs requested a separate enumeration of the Particularly Vulnerable Tribal Group (PVTGs) within the Scheduled Tribes (STs) for the upcoming 2027 Census. The demand for updated data on PVTGs grows because many of these communities were undercounted in earlier Censuses. Accurate data is vital for fulfilling constitutional duties, ensuring inclusion in national statistics, and developing targeted welfare policies.

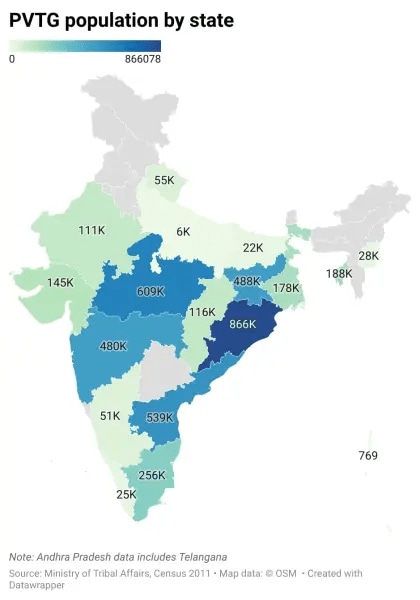

The PVTGs, known as Primitive Tribal Groups prior to 2004, were first identified by the Dhebar Commission as communities characterised by “pre-agricultural technology, low literacy rates, economic backwardness, and declining populations.” India recognises 75 PVTGs across 18 states and UTs.

However, recently, it became a boiling issue when the Centre proposed a “Non-Invasive Thermal Census” of the Sentinelese on North Sentinel Island, a community characterised as “hostile” in official records — who prefer “isolation” and are “unwelcoming” towards any outsider intrusion.

Recent years have seen an increase in attempts to contact the Sentinelese, raising concerns about the effectiveness of tribal protection efforts. Notable incidents include the 2018 Allen Chau case and the March 2025 arrest of US citizen Mykhailo Polyakov during his third attempt to reach uncontacted Andaman tribes. Throughout history, romanticised perceptions about the Andamanese tribes have fueled curiosity to know the unknown and have consequently threatened their survival. Colonial expeditions previously decimated their population, silenced their languages, and fragmented their culture, reducing the Great Andamanese from 5,000 to approximately 50, and the Onges to a dependent community. The Andaman & Nicobar Islands Protection of Aboriginal Tribes Regulation, 1956 (ANPATR), legally safeguards the tribes’ choice of isolation and protects them from external contact. Since Scheduled Areas don’t apply here, ANPATR ensures tribal protection and aligns with non-interference policies. Activities like counting uncontacted tribes may be a starting point to violate this essence of protection.

The Centre’s use of “Non-Invasive Thermography” to Census the Sentinelese is another step towards knowing the unknown. Thermal counting by drones or aircraft will create noise and record images, potentially violating regulations that protect the tribal choice of isolation, dignity, and cultural rights within the state’s official buffer zone and zero-contact policy. However, advocates of this counting process argue that drones and infrared imaging can “count without contact,” aiding land mapping and wildlife surveys under the SVAMITVA scheme. These efforts overlook a history of colonial and post-colonial intrusions.

Counting the Sentinelese is not merely an administrative venture; it is just the beginning of the process experienced by the other tribes in the Andaman. T N Pandit, who spent five decades studying these tribes, warned that such attempts cause irreversible damage to a culture determined to remain unseen and untouched. A community that can survive massive natural disasters, such as the 2004 Tsunami, with its traditional knowledge system, which recognises the warning signs encoded within it when the non-tribal population and modern technologies feel helpless, also has the ability to survive further.

The state’s desire to count its citizens can be understandable. However, there are occasions when it becomes an act of violence against uncontacted cultures, such as the Sentinelese, who have consistently demonstrated that their isolation is not only a choice, but rather, is an essential means to protect their culture from any form of intrusion.

Since colonisation, these tribes have been perceived as a menace to development, peace, and good governance, with priorities often given to nationalist discourse of strategic and economic interests over tribal protection. The Andamanese tribes’ different approach towards outsiders is not only due to their geographical and physical isolation, but also past experiences, which contrasts with that of mainland Indian tribes, who have maintained some relationships with the non-tribal population throughout their history. That’s why they require cautious protection and consideration within legal and administrative frameworks to build trust, and, most importantly, preserve their culture.

Before deploying its drones and algorithms, the state must face this simple truth: A vanishing and vulnerable culture does not need to be counted, but to be recognised. Their worth is not statistical but rather a cultural being who chooses to survive without interference. Respecting their autonomy affirms cultural dignity and reminds us that true progress sometimes lies in restraint. As a welfare state, India should honour the culture of its vulnerable and isolated communities and safeguard them through its legal framework or whatever measures are necessary; otherwise, the cost of curiosity to count the uncontacted will be high.

The writer is a PhD Scholar at the Department of Political Science, University of Delhi, working on Andaman Tribal Policies