It is a measure of the cynicism and complacency that marks world politics that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is fading away from global consciousness as just another fact of life, obscuring the human costs and the risks of the conflict. The initial reaction to the attack was panic. Could this escalate into a wider war, or worse still, into a nuclear confrontation? It was feared that the implications for the global economy might be catastrophic. And there was some concern for the fate of Ukraine itself.

A year after the invasion, there is marked complacency about the risks of escalation. The NATO strategy was to arm Ukraine to defend itself but avoid a direct military confrontation with Russia. It was to try and make sure the war did not spill over to a wider geography, and that a combination of western unity and economic sanctions would be the means to pressure, if not cripple Russia. NATO calibrated its military support to achieve these objectives. A year later there seems to be growing confidence that this fine line between supporting Ukraine and directly confronting Russia can be maintained. But as with all security threats, the line may be in the eye of the beholder. It is not an achievement one can take for granted.

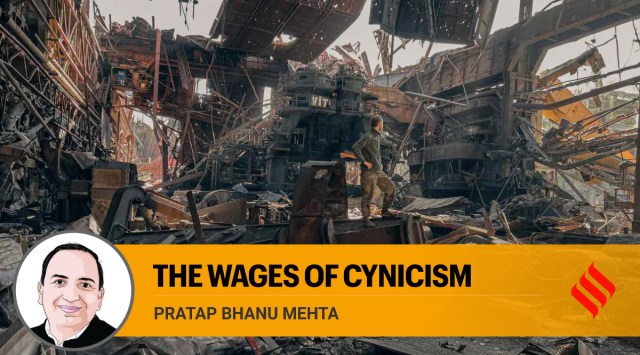

The biggest surprise in the months following the invasion was the heroism of the Ukrainian resistance against a brutal Russian onslaught. In some ways that resistance was an extraordinary achievement. It at once exposed the brittleness of Russia’s military power. But as the war enters its second year there is now a greater risk that it could be even more brutal and its humanitarian costs catastrophic. The Ukrainian resistance was enough to push back the invasion. But it is not entirely clear that it will be militarily in a position to declare total victory by reclaiming Crimea and Donbas. In the meantime, what is becoming clear is that Russia has also redoubled its resolve despite catastrophic losses in the first year. It escalated by calling for a general mobilisation. But perhaps even more ominously, it could increase the destructive power of this war even further by escalating missile strikes and targeting civilian infrastructure in Ukraine. If it looks to President Putin like he is losing, the will to destruction could intensify even further. This will not break the Ukrainian resolve. But it does suggest the alarming possibility that we may not have seen the worst of this war yet, even if Ukraine grows to strength or despite it making gains.

The initial uncertainty over the larger economic fallout of the war has subsided. It is now seen as nothing more than a temporary shock. Aided by a warm winter, Europe readjusted its energy supplies. Predictions about catastrophic inflation did not come to pass. What the war did was unleash a new round of opportunism around the world that reoriented energy flows, created new currency swap arrangements, realigned future defence production. But it also turned out that economic sanctions were a feeble tool against Russia. As the historian of economic sanctions, Nicholas Mulder, pointed out, Russia’s economy shrank but far less than the world had expected. Thanks to much of the world outside of the West and some deft management, Russia can sustain an economy where the effect of sanctions on its population is not catastrophic, and at least a destructive war can be waged. The really challenging question will be whether Ukraine’s economy will be easy to sustain if Russia’s will to destruction continues.

One of the tragedies of the war is that for most of the world, Ukraine remains the sideshow, collateral damage in that inevitable drama of great power competition. There is good reason to be cynical about framing this conflict in excessively moralistic overtones like the preservation of the liberal world order or a conflict between autocracy and democracy. If anything, the war has tied the US hands even more in acting as a policeman of liberal values. It has given its friends and allies like India and Israel even more cover to renege on their democratic promise, without attracting any international attention. For most of the world, the war became an occasion for Schadenfreude about American power. It was viewed as a consequence of America’s hubris in not accommodating Russia’s security concerns. We can endlessly debate the matter. Or else, the recent history of American interventions made the Russian intervention just another one of those bad things all great powers do.

This was a wonderful time for everyone else to be opportunistic. But what got lost was the specificity of the Russian invasion. It is probably the first time since World War II (with the possible exception of Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait), that the object of an invasion was not simply to brutally annex territory or produce regime change, but to obliterate the existence of a whole country. In this sense, the Russian invasion was not just a rerun of great power completion, it set a whole new norm. But this fact and the tragedy of Ukraine became a sideshow for the rest of the world.

The Ukraine war emerged out of a combination of four things. A great power rivalry in which Russia felt the US had not accommodated its security concerns and was encircling it; traditional territorial claims; the confidence on Russia’s part that it could win, but if not, at least America was not in a position to make its writ run on the world, and an authoritarian figure determined to leave his mark on history. As balloons hover over the US, and US ships circle around China, there is an analogous danger. The US is creating an alliance to deter China, a coalition that more effectively brings power to China’s doorstep. Like with NATO expansion, will this security coalition actually deter China or convince it that there is a threat here to be answered preemptively? Can the delicate needle between deterrence and offence be threaded? The Chinese are engaged in price discovery to see what they can get away with. So the risks of direct conflict are escalating. The incipient economic sanctions on China are underway. China’s long-standing historical and territorial claims over Taiwan remain a potent ideological factor. And China also has a leader determined to leave his historical legacy. The casualty of the cynicism and complacency that the Ukraine war has produced is that not only will the unfolding catastrophe in Ukraine become invisible, the world might also sleepwalk into another war, by trying to be too clever by half.

The writer is Contributing Editor at the Indian Express