One morning, as I, Martin Macwan, was debating whether or not to go for a seminar on atrocities against Dalits, I glanced at my mail. My friend Shankar had sent me a news story about a Muslim girl in a small village, Lunva, in the Kheralu Taluka district of Mehsana in Gujarat. The girl was not honoured by her school although she was the top scorer in Grade 10.

As I, Syeda Hameed, was looking through an Urdu paper, in a corner of the front page, I read the same story. I could not believe it. Then my phone rang. It was Martin: “Apa, I am on the road, heading to Lunva, Mehsana…”. After that both of us were silent; nothing more needed to be said.

I, Martin, reached Lunva, 125 km from Ahmedabad, with my colleagues Shantaben and Bharatbhai. Upon reaching, the village sarpanch accompanied us to the student, Arnaz Banu’s house. We were offered water by her family which we drank. They said that the village has 80 Dalit and 400 Muslim families. Fifteen-year-old Arnaz Banu lives with her 85-year-old grandmother Mehrunisa, her parents Sanewar Khan and Sohana Banu, her sisters Unesha Banu, Arina Banu and youngest brother Ziyan.

Sanewar Khan Sipai was trying to hold back tears as he spoke. A few days ago, he went to collect his daughter’s marksheet. The principal informed him that Arnaz was the top scorer in the school in her SSC board exams. All this while, as we were speaking with her husband, Sohana stood tightly holding the door; her tears flowing. On our request, Arnaz came out and sat on a cot along with my colleague Shantaben.

Arnaz’s eyes were swollen and red. Her tears flowed off and on for over two hours while we were there.

Arnaz was the top scorer (78.86 per cent with a 91.60 percentile rank) in her SSC board exams held in March 2023, among all the students of her school, K T Patel Smriti Vidyalaya. The school has an old tradition of honouring students who have ranked first, second and third in the SSC board exams on August 15 — during Independence Day celebrations. The school also records the name of the top-scoring student in their school on a publicly-displayed honours list.

On Independence Day, Arnaz looked forward to being publicly honoured. Her mother dressed her for the school function. The school principal ascended the stage and announced the names of the top scorers. “The second, third and fourth position in the 2023 SSC board exams…”, he began, in a loud voice. But where was number one? The top scorer, number one, was missing. All eyes were on Arnaz — her friends, Hindu and Muslims, all expecting her to be called first.

As soon as the function was over, Arnaz rushed home. Dissolving in sobs, she told her mother that it was better if she had not studied at all. Her father and mother consoled her, unable to bear the pain of their child. The entire family felt the humiliation.

As we were talking to them, we saw a crowd approaching their courtyard. “These are our friends, our Dalit neighbours,” Sanewar told us. We learnt that in this village, Dalits and Muslims visit each other on social occasions. Glasses of nimbu sharbat and tea were served to all of us by the daughters.

One of the visitors, Dasrath Bhai, a Dalit, told us that in 2019, his daughter Nisha was the top scorer in her SSC board exams. She, like Arnaz, was not honoured by the same school; though her name was displayed on the honours board. Dasrath Bhai is a landless farm labourer earning his livelihood from labour and animal rearing. He said nothing, did nothing when Nisha was not honoured. For him, this was normal; being a Dalit, this was normal, routine, common, standard way of life.

Sanewar Khan, a 12th-class graduate, is a small farmer who owns 5 bighas of agricultural land. Due to the lack of irrigation water, he does sharecropping with others. His farm borders the school premises. He is a member of the School Management Committee; some people suspected that Arnaz’s good performance was due to her father’s presence in the SMC. The board exam’s results silenced them.

Unesha Banu, Arnaz’s older sister, is in Class 12 in another school in the next village. She is now persuading her younger sister to join her school, which she says is better. Their parents have mortgaged their farm this year for Rs 1 lakh to ensure that both daughters can study further.

After suffering this humiliation, Sanwar Khan immediately registered his protest with the school authorities. The latter, under pressure due to media coverage, fumbled for excuses. They said they would publicly honour Arnaz on January 26. When we asked Arnaz about this, she said, simply, “The school has never ever held such a function on 26th January”. As we left, we asked Arnaz, “What do you want?” “Justice,” she said softly.

I, Syeda Hameed (with my usual anxiety about news about Muslim bashing), read the front page of an Urdu paper. There it was! A few days ago, at Jantar Mantar, the All India Sanatan Federation held a Mahapanchayat. It was led by Yati Narsinghanand of Dasna and Vishnu Gupt of the Hindu Sena. More than 100 Hindu “organisations” participated. The police acted quickly to disburse them but only after they had made their points. What were the points? “If Muslims are allowed free reign, then in 2029, India’s Prime Minister will be a Muslim”. “All Muslims should go to Pakistan. Even if one single Muslim remains in India, we Indians will not accept Partition of Akhand Bharat”. The additional DCP said that the police instructed them to refrain from “nafrat angezbayaan” (hate speeches) in view of the SC directive. Despite this, despite the poison emitted by the speakers, there is one inexorable fact: No FIR was registered.

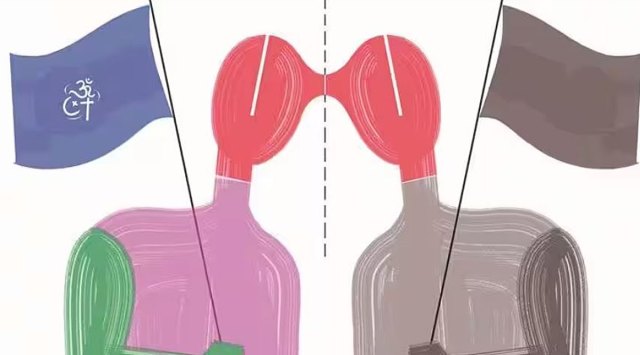

I, Martin, and I, Syeda, hope that a huge tsunami of our fraternity, exemplified by Sanewar and Dasrath rises to drain the lethal poison engulfing our beloved country.

Macwan is Founding Member of Navsarjan Trust. Hameed is Founding Member of Muslim Women’s Forum