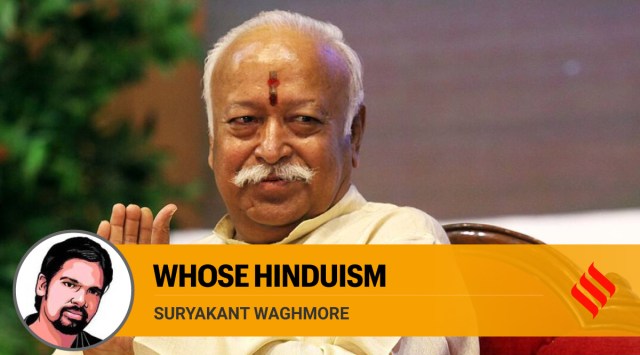

At a recent event to celebrate Sant Ravidas Jayanti in Mumbai, Mohan Bhagwat, the Sarsanghchalak (chief) of the RSS once again emphasised that caste is “bad” and even went on to say that priests (Brahmins) were responsible for the creation of caste, and not god. In the same speech, he called for refraining from conversion to other religions in search of equality.

A foundational problem with those who put faith in Hinduism to fight Hindutva is their overlooking of the caste question. Contrary to popular Hinduism, Hindutva has historically pursued a nationalist critique of caste and has thus been part of the Hindu modernising/reform process. Contemporary forms of engagement and accommodation of “impure” castes in Hindutva’s ideology-building unravel the making of Hinduism as a civil religion. This is decidedly different from popular Hinduism and its ontological basis. Such a version of inclusion is, indeed, not egalitarianism; rather, it is an alternative version of hierarchy that promises a reversal of the estrangement of non-pure castes in popular Hinduism.

Contemporary politics of inclusion and broad-basing in Hindutva even involve the occasional invoking of Ambedkar, only to be depoliticised and turned peripheral in the praxis of the RSS. Caste is, however, not frequently mentioned as part of a “great” ethical past anymore, and discrimination on its basis is increasingly recognised as a problem to be dealt with. As the Ambedkarite and Mandal movements revolve around caste as structural inequality, Hindutva constructs Hinduism as a civil religion, not necessarily bound by caste anymore, but as a step towards mobilising various castes in favour of nationalist Hinduism.

The RSS has been occasionally denied the status of an “association” in civil society and some liberals even suggest that the RSS does not constitute civil society as it fails to generate social capital for democracy. However, in its attempt to construct Hinduism as a civil religion, the RSS does construct an alternative civil society. Sociologist Robert Bellah suggests that civil religion need not impinge on private religion, and it is not always invoked in favour of worthy causes — it is a set of beliefs, symbols, and rituals that exist alongside, and is rather clearly differentiated from the churches.

Hindutva, while attempting to turn Hinduism into civil religion, nationalises rituals and deities and constructs an inclusive, nationalist Hinduism, which is very different from popular Hinduism that is embedded in caste hierarchy and distinction. Naturally, Bhagwat’s remarks upset the Shankaracharya of Puri.

Can Hinduism be a civil religion? Alexis de Tocqueville, a prominent white, European philosopher of democracy felt that Islam represented an aristocratic civil religion and that Hinduism was an uncivil religion (petrifying effect, civilisation stops itself before belief, piety without morality, immaterialism, turns followers into pacifists). De Tocqueville seems to sum up Hinduism as a religion of superstition. Among Indian thinkers, Ambedkar too was a major sceptic of the democratic possibilities in Hinduism and the making of a genuine “Hindu public” was simply impossible for him.

Hinduism in its popular practice lacks the universal salvation philosophy of solidarity and may seem more like a collection of castes that occasionally unite for political and ritual purposes. Hindutva, on the other hand, seeks to actively unite the divided and hierarchically-ordered castes under the rubric of Hindu unity. The fear of the “other” (Muslims and Christians) mostly dominates such mobilisation, along with cow protection and localised communal conflicts.

Hinduism as a civil religion is a nationalised religion, one where the territory of India and a “thin” and abstracted notion of Hinduism are merged to create a new common space that can mediate between the localised communities of sects and castes. Hinduism is turned national here as an accommodative and civil religion for all Hindus, and Hindu Manushyata (humanism) is invoked to counter westernisation and internal “divisions”.

The making of Hinduism as a civil religion also points to a new Hindu consciousness among the lower and marginal castes, which counters the estrangement that popular Hinduism creates. While liberal Hindus hope to use Hinduism to counter Hindutva, Hindutva is slowly countering the ills of Hinduism by framing and promoting it as a national civil religion.

Caste, however, is not just localised but integral to the metaphysics of Hinduism, and Hinduism as a civil religion continues to find it difficult to overcome caste. Ambedkar recommended, instead, the path of conversion out of Hinduism into Buddhism in search of a genuine civil religion for caste-ridden India.

The writer is professor of sociology, IIT-B