The world over, challenges confront parliamentary democracy. The challenges emanate from the multiplicity of identities — from interests and aspirations of different socio-cultural and religious groups competing for recognition and representation. We must acknowledge that multi-ethnic and/or multi-religious societies often have deep-rooted historical, cultural, and social differences between various groups. These divisions can and do lead to political polarisation and hinder the formation of a nuanced consensus on significant concerns likely to impact everyone. A robust and inclusive public sphere is, therefore, a necessary precondition where such differences could be discussed and mended instead of trying to hold them in silos or, much worse, curbing their free expression. Without such differences being addressed proactively, there is always a risk of them festering and erupting in different ways. Some of our most serious contemporary issues have needlessly become contentious, even violent because there is an overarching tendency to use polarisation as an ideological tool, an electoral strategy. What is instead required is the political will and outreach to assuage the concerns of various competing groups and create an enabling environment for dialogue and debate.

What we have seen in India is quite the opposite. The polarisation in society has caused discernible fragmentation within Parliament as well. In a country like ours, where a good number of states are being ruled by parties that are not in the ruling coalition at the Centre, the adversarial position between the ruling parties at the Centre and the state level is causing frequent disruptions in Parliament.

Under these circumstances — as has been the practice the world over and in India — the onus of the smooth functioning of Parliament is on the ruling party at the Centre. The problem arises only when they apply the power of the legislative majority to the entire form and content of parliamentary strategy and resist the wisdom of listening to the other side. If the majority party dominates the political landscape even inside Parliament, it leads to the exclusion of voices of the Opposition. The role of non-partisan facilitators in this context becomes crucial.

Non-partisan facilitators must ensure that all members, regardless of their political affiliation, are treated fairly and given equal opportunities to participate in debates and discussions. Maintenance of order and decorum during parliamentary sessions is also another area they could greatly improve. Non-partisan facilitators must uphold the rules and procedures of the legislature without leaning towards any political party. This ensures that debates are conducted in a civilised manner and the focus remains on discussing issues of public importance. However, in cases where the actions or inaction of leaders cause a situation with overwhelming crimes against humanity, simple adherence to the rule book shall not help Parliament. It shall expose the hollowness of our posture of being the “largest democracy” in the world.

The test of true democracy is how free we are in taking up issues in Parliament even at the cost of unsettling the rigid position of the ruling party on any issue of national concern — or when the society confronts “crime against humanity”. A political climate which celebrates “unfreedoms” cannot call itself free and fair to all sections of Parliament. It is against this backdrop that the precedence, as well as traditions of the Indian Parliament, must be interpreted and applied. We need to keenly study and understand how other democracies function in similar situations. Non-partisan facilitators help safeguard the independence of the legislature. They can act as a check on the executive branch’s influence and prevent any undue interference in the functioning of the legislature.

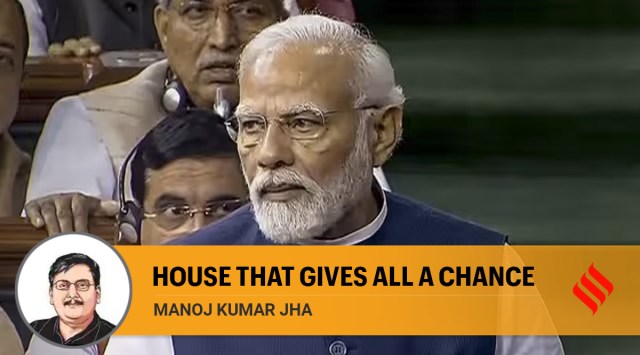

Non-partisan facilitators play a crucial role in upholding the rule of law within the parliamentary system. They interpret and apply parliamentary rules and procedures fairly and consistently, ensuring that the legislative process is conducted by established norms and principles as well as traditions of the House. We should not forget that Ganesh Vasudev Mavlankar’s bell used to ring for Jawaharlal Nehru as well if he exceeded the time allotted to him. There are several such instances when the Chair reprimanded important ministers from the cabinet if their behaviour was found to be belittling the important position of Parliament in our democracy. The present regime, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, can borrow some insight from Jawaharlal Nehru. He commanded a much more comfortable majority than Modi in the House. Yet, he knew that if he failed to respect the feeling and opinions of the Opposition, he shall be doing the greatest disservice to parliamentary democracy.

That brings us to the fact that has been overlooked in recent times: Non-partisan facilitators must follow the likes of Mavlankar and rise above their political affiliation or ideological inclinations. They may have huge admiration for the PM or any other cabinet minister but the placement of the Chair in the middle means they must set aside their predispositions to safeguard democracy.

We need to bring back that kind of public confidence in the keepers of our democratic institutions. When citizens see that the people overseeing the legislative process are impartial and fair, it reinforces their trust in the democratic institutions and the overall governance system. Failure to weigh in dispassionately in facilitating a broader consensus amidst conflicting perspectives between the treasury benches and the Opposition erodes public trust. It is time for all of us occupying space and entrusted with governance responsibilities to revisit the idea of democratic spirit and protect opinions that may not be in sync with the viewpoint of the ruling party but are worth listening to.

Once such an environment is in place, it will not only ensure the effective functioning of parliamentary democracy but will go a long way in promoting transparency, fairness, and accountability within the legislative process. Despite a fragmented polity, it will also help maintain the integrity of the democratic system and strengthen the principles of deliberative democracy.

The writer is Member of Parliament, Rashtriya Janata Dal