There is a Bengali term reserved for a special kind of Bengali people: “Rowakbaaj”, or those who frequent the rowaks of Kolkata. The red-oxide rowaks, a distinctive feature of north Kolkata homes, are just an elevated platform that run along house fronts. This is where not-so-busy, young (and not-so-young) men would gather to mainly gossip and debate about anything under the sun. They are, of course, derided by everyone around them. They have a streak of rebellion about them that makes them perfect protagonists for rehabilitating-the-hero dramas. Late on Vishwakarma puja nights, you can catch them drunk dancing specifically to the Bappi Lahiri classic, ‘Yaad Aa Raha Hai’ from Disco Dancer (1982). There is a special kind of loneliness in their eyes then, a lament for all things that was denied to them. For the longest time, the term rowakbaaj was interchangeable with “Mithun fans”.

Mithun Chakraborty, a Bengali hero in a crowd of fair-as-makkhan north Indian stars, who, with his unbuttoned shirts, billowy bell bottoms and side-parted locks, inspired a generation of Kolkata rowakbaajs to dream. It is little surprise that he still is such an icon here. Growing up in the “narrow galis” of Jorabagan in North Kolkata in the 1960s, which can barely accommodate two people walking side by side, Chakraborty embodied a generation of Bengali men. Restless, angry and full of swag. It was probably that restlessness that made him participate in the Naxal movement. An uprising that ignited a fire in the hearts of both the urban youth and the rural masses in the 1960s. It was a movement that appealed to the urban youth, particularly students, because it exemplified the precise way in which the establishment could be challenged.

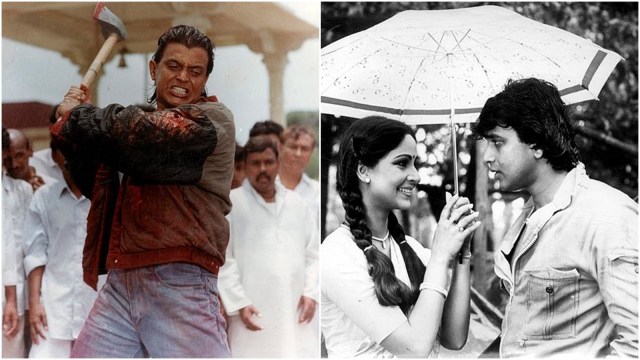

Chakraborty was quickly “rehabilitated” after the death of his brother in a freak accident. This rehabilitation involved a film course in FTII Pune. And the rest is history. But by then, Chakraborty had imbibed everything the mean streets of Kolkata had to offer. The glare, the swag, that spring in his step and that specific way of talking, like he had nothing to lose. These qualities were exploited with varying degrees of success by Bollywood makers, who cast him as the dancing hero, the dancing spy and the dancing vigilante. Meanwhile, in Bengal, in the lanes where he grew up, Chakraborty was defining the way young men of a certain disposition viewed themselves. So what if they had dropped out of school, so what if they didn’t have a job, so what if their parents taunted them. If Mithun can achieve startling success, so could they. Mithun’s stardom was personal to them. Meanwhile, the bhodrolok middle class had an uncomfortable relationship with Chakraborty. He was the guilty pleasure they couldn’t own up to. He stood for everything that they warned their children against. The hair, the generous display of man chest, the tight pants.

Even as video cassettes of Dance Dance (1987) and Kasam Paida Karne Wale Ki (1986) flew off shelves of video libraries, your teachers chided you for your “Mithun cut” hairstyle. His songs were definitely kosher for school and Durga Puja functions. Decent boys and girls didn’t gyrate to “Zubi Zubi” (Dance Dance) on stage. They were reserved for late night drunk dancing of para rowakbaajs.

But Mithun, time and again, tried to woo this very bhodrolok audience with films like Tahader Katha (1992). In this arthouse Buddhadeb Dasgupta film, he played an ageing freedom fighter who doesn’t know what to do with his life after being a political prisoner for decades. Chakraborty won his third National Award for the film. He had won a Filmfare Award for Agneepath (1990) just a year earlier. Tahader Katha won him laurels but Mithun da was still Mithun da. A year later, in 1993, he was gyrating to “Gutur Gutur” from the 1993 film Dalal. A song that had the dubious distinction of being termed the most “vulgar” Bollywood number of the year, in the same year that had “Choli ke peeche kya hai” (Khalnayak) and “Sarkai lo khatiya” (Raja Babu). A few years later, Mithun played the revered spiritual guru, Swami Paramahansa in the 1998 film Swami Vivekananda. He won his third National Award for the film. That very year, his cult hit Gunda released to empty halls. The dialogues of the film still inspire memes galore.

Chakraborty’s brush with politics didn’t help either. The actor, who was known to be close to Naxal leader Charu Majumdar, was reportedly close to Left leader Jyoti Basu, but in 2014 he joined TMC. In 2021, he joined the BJP. Shifting allegiance from ultra left to ultra right.

Yet, news of him being conferred the Dadasaheb Phalke award is met with celebrations across Kolkata. In his para, Jorabagan, old neighbours are distributing sweets. I suspect there will be some drunk swaying to “yaad aa rahi hai” today .

premankur.biswas@indianexpress.com