As the police began its crackdown on Waris Punjab De and its chief Amritpal Singh in Punjab last week, many sought to draw parallels between the present situation in the state and that of the early 1980s. But nothing could further from the truth. Those were very different times. But then, like now, there was a chase of sorts.

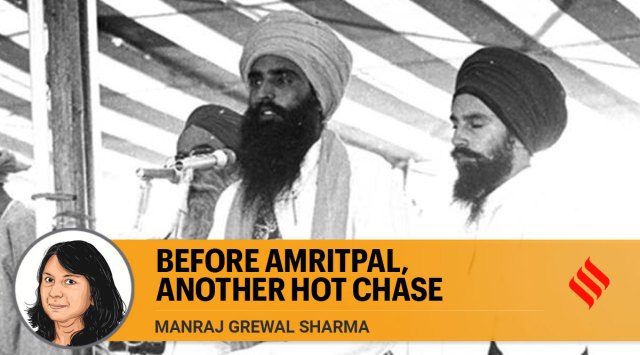

It was in September 1981 that the Punjab Police decided to arrest Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale, head of the Sikh seminary Damdami Taksal, for his alleged role in the conspiracy to assassinate Lala Jagat Narain, a Member of Parliament, and chief editor and proprietor of the Jalandhar-based Hind Samachar Group of papers, who was shot dead on September 9.

Prof Jagroop Singh Sekhon, a political observer with a long academic career at Guru Nanak Dev University, Amritsar, remembers how Bhindranwale’s eventual arrest took place against the backdrop of the battle of political one-upmanship between then Union home minster Giani Zail Singh and Punjab chief minister Darbara Singh, both from the Congress party. The latter negotiated with Bhindranwale for his surrender, who put up a list of preconditions.

In his book, Turmoil in Punjab, Ramesh Inder Singh, who was then deputy commissioner of Amritsar in 1984, wrote how Bhindranwale refused to have anything to do with DIG J S Anand, who was first sent by the state government for a dialogue on his arrest, just because he had trimmed his beard and was hence not a ‘pure’ Sikh. The state government acceded to his demands, and sent an SP-rank officer who met Bhindranwale’s standards and got him to agree to surrender on September 20. That day also saw what is arguably the first case of indiscriminate firing by militants at Jalandhar in which four persons were killed.

The preacher declared that he wanted to be taken to the Golden Temple to pay his obeisance and take a dip in the holy sarovar before he is arrested.

Accordingly, a senior DIG-rank police officer drove him to the temple and back before daybreak on September 20. By then, a mammoth crowd had gathered at Chowk Mehta near Amritsar, headquarters of the Damdami Taksal, and leaders cutting across party lines gave fiery speeches lauding Bhindranwale.

Upon his arrest, the crowd, already fired up by the speeches, turned violent and clashed with the police, which opened fire, killing eight persons.

Ramesh Inder Singh writes that then CM Darbara Singh, apprehending trouble, had requested for Army help, both from the Centre and the Western Command, but did not get it.

High drama surrounded Bhindranwale’s imprisonment as well. In his book, Living a Life, Ravi Sawhney, a former Punjab bureaucrat, recounts the state’s flip-flop on the plans laid out to make a it a smooth affair. Since the news got out that he would be held in the Ludhiana district jail, a large number of people turned out to welcome him. There was an air of festivity with welcome arches at the entrance of the city.

Sawhney, who was then deputy commissioner of Ludhiana, says he decided that they would divert Bhindranwale’s car from the convoy bringing him to Ludhiana and hold him in a secluded guesthouse. But this plan was shelved half an hour before Bhindranwale’s arrival when he was told by the then SSP that there were orders from the state police chief to let the preacher’s car enter Ludhiana along with a convoy of police vehicles. Sawhney writes how he called up the CM, who, in turn, told him that the orders had come from none other than Giani Zail Singh. As expected, the convoy turned into a procession as people followed it in various modes of transport and pro-Bhindranwale slogans filled the air.

As demanded by him, Bhindranwale was escorted by Gurdaspur SSP Chahal, who came with a list of instructions given by the preacher. Sawhney writes, “Bhindranwale was still sitting in the Ambassador car with two companions when Chahal came across to where the Deputy Inspector General, Police, Patiala Range, SSP Bhatti and I were discussing security arrangements to convey the conditions Bhindranwale had attached to his surrender.”

In his book, Sawhney then goes on to list Bhindranwale’s conditions:

1. Two companions, his cook and his sewak, would stay with him

2. When he is interrogated, it must be only by a gursikh (a Sikh who observes all five tenets of Sikhism)

3. When he is interrogated, he should be sitting at the same level or higher but not lower than the interrogator and

4. If he chooses not to answer any question, no third degree method should be used.

“I listened aghast and quipped to Chahal, ‘Who is under arrest, Bhindranwale or the Punjab government?,’” wrote Sawhney.

Later, the police failed to find any evidence against Bhindranwale and he was set free on October 15, 1981. The state, however, continued its descent to violence that consumed it for over a decade.