As I read reports about the suspension of Nahid Siddiqui — the principal of a government school in Bareilly — and an FIR being lodged against him for making students sing Mohammad Iqbal’s poem, Lab Pe Aati Hai Dua, I was filled with a deep sadness. According to media reports, the FIR has been lodged on the basis of a complaint by a local functionary of the Vishwa Hindu Parishad for the recital of a “religious prayer” in a “bid to convert the students”. Vinay Kumar, the Basic Shiksha Adhikari of Bareilly, said, “A prayer was being recited which said something like ‘Allah ibadat karna’. This is not the stipulated prayer and hence, school principal Naheed Siddiqui has been suspended”.

In these viciously polarised times, an action like Siddiqui’s suspension is passe. Perhaps, persons of goodwill would be grateful that he was not physically harmed and that his services were not summarily terminated. So why are my feelings as cold as the winter’s chill?

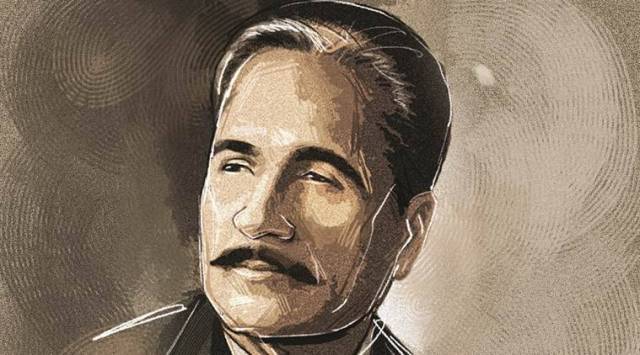

Iqbal’s poem is evocative for it gives expression to a child seeking divine benediction to follow the path of goodness, to care and have affection for the poor, the needy, and the weak, to be a source of light and spread that light in the darkness, to be a flower in the nation’s garden, to love the flame of knowledge. Surely, no objection can be taken to any of these wishes and prayers. The “offending” stanza is the last one where the child says, “Mere Allah burai se bachana mujhko, nek jo rah ho ussi rah pe chalana mujhko”. The words “Rab” and “Khudaya” may also be found offensive by some, as they may consider them alien, though they are commonly used by at least some Hindi — or Hindustani — speaking people.

Iqbal inspired the Pakistani movement and was for reformed and even assertive Islam. He and his family were Kashmiri Pandits before they became Muslim. I learnt this from my maternal grandfather “Chand”, a Kashmiri Pandit himself. His family home was in Lahore until Partition, and he was an Urdu poet and an administrator. He considered Iqbal his ustaad. He told me that when he recited a couplet he had composed to Iqbal:

“Uth gaya parda to phir mehmil na tha, Laila na thi/Ek farabe deed ko aapna jahan samjha tha mai”

(“When the curtain rose there was neither Laila’s seat nor Laila herself/What was illusory, I had considered to be my world”)

Complimenting “Chand”, Iqbal told him that he had summed up the entire Vedanta in a single couplet for the essential meaning is: This world is but an illusion. My maternal grandmother, a daughter of Tej Bahadur Sapru, told me that Iqbal’s family were Saprus before they took to Islam. She also said that as Iqbal drifted towards Pakistan, her father had chided him but had had no impact on Iqbal.

I have, however, meandered. What is under consideration here is not Iqbal’s politics and not even his “diwan” as a whole but this beautiful poem of a child praying to the divine to lead them on the path of goodness. A friend who has studied in one of India’s finest public schools tells me that this poem was part of a collection of poems from which recitals were made. It is doubtful any student of the school was inspired to embrace Islam because of it.

I went to a school run by Roman Christian missionaries and twice a day, the Lord’s prayer was recited. The vast majority of the school’s students were Hindus but there were others too — Muslims and Sikhs included. All of us recited the same prayer. Yet, no non-Christian became a Christian. Innumerable students who went to schools run by Christian missionaries of different denominations all over India share this experience. I have not heard of anyone who went to these schools becoming a Christian.

So, from where has this fear of the very use of the words Allah or Jesus Christ arisen? History bears witness to the resilience of Hindu culture and religion, not having allowed Islam to sweep all away as it did in other lands and with other civilisations. Why have we reached a pass where our basic civilisational principle of openness is being eroded? And why are we so offended at the recital of a prayer which mentions Allah? Is our confidence in ourselves and our faith so fragile that the very mention of Allah in a poem is objectionable? It never was. Even when Indo-Persianate culture had extensive influence, at least, in large parts of urban India, Hindus believed in the intrinsic merit of their faith and civilisation. That is how I have always interpreted Iqbal’s verse,

“Iran-o-Misr-o-Roma sab mith gaye Jahan se/Kuch baat hai ki hasti mitti nahi hamari”

(“The old Persian, Egyptian and Roman civilisations have disappeared from the world/But there is some unique strength in our identity which has not been erased”)

It matters little to me what Muslims do — and I do think that their objections to Vande Mataram, for instance, reveal their civilisational insecurities. Sadly, the more educated among them are not combating attempts being made towards closing of the Muslim mind. However, as a proud Hindu, what matters to me is that we should not lose our essence of openness. That is what made us “authentic” and that was what “grounded” us to our civilisational roots. Authenticity and remaining grounded spring from a confidence that is beyond language and dress and the drama of our times.

Finally, how can we forget that Mahatma Gandhi, the father of our nation, modified the famous bhajan Raghupati Raghav Raja Ram by inserting the words “Ishwar Allah tero naam”? This was done during the Dandi March. At least one right-wing writer has taken objection to Gandhiji’s modification — and in words that I can never bring myself to repeat. But it is still one of the main bhajans sung on different occasions, including October 2 — Gandhi Jayanti. Should we now look to file an FIR against any person who sings Gandhiji’s version of the bhajan because the original rendering does not have the words “Ishwar Allah tero naam”?

The writer is a former diplomat