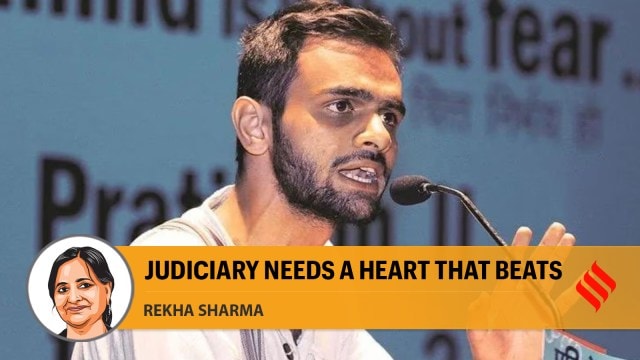

Bail is the rule and jail is an exception. Nearly 50 years ago, the Supreme Court stated it; there have been cases where bail orders were passed late at night. However, time has changed. That salutary rule is now being followed more in breach than in compliance. Thus, when the Delhi High Court, by its order on September 2, declined to grant bail to Umar Khalid and nine others who have been in jail for nearly five years, it was no surprise.

If one were to agree with the solicitor general, they need to remain in jail till the end of their trial, which, even after a lapse of about five years, has not started. So what if Umar Khalid has been languishing in jail? So what if his bail application was tossed around in various courts — from the trial court to the Supreme Court — and was finally heard and dismissed by the Delhi High Court? So what if the Supreme Court has consistently held that the right to speedy trial is a fundamental right under Article 21 of the Constitution, emphasising that delays violate personal liberty? So what if the Supreme Court is telling us that even a day in prison is a day too many? So what if he is acquitted after years of incarceration? Recently, in the case of the 2006 Mumbai train blasts, the Bombay High Court acquitted 12 accused, holding that the prosecution had utterly failed to establish that they had committed the crime. What about the days lost and the dreams shattered? In Khalid’s case, five long years have passed; the chargesheet runs into thousands of pages, and is still not a fit case for bail, more so when we are told that “Bail, not jail, is the rule.”

Let Umar Khalid and the likes of him not forget that they are not a Pune businessman’s son who allegedly killed two motorbike riders while driving a Porsche car in an inebriated state and was released on laughable bail conditions of writing an essay on accidents and working with the traffic police. Let them not forget that they are not Asaram Bapu or Gurmeet Ram Rahim Singh, who are in and out of jail despite being proven guilty of murder and rape. In the words of Alfred Lord Tennyson, though said in a different context, “they are not to reason why, they are but to do and die”.

The lament is not about Umar Khalid. No one is standing by him, and nor should anyone stand by him if he has committed any act of terrorism. He must be punished as per the laws of the land, however harsh and stringent they might be. But not till he is proven guilty. In the meantime, the process itself should not become a punishment. It should not be used as a weapon to dehumanise. The lament is about people becoming dismissive of the courts.

Unfortunately, it is not just the citizens and politicians who are critical of the judiciary. The voices of dissent have been emerging from within as well. In 2018, four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court in a press conference raised an alarm against the functioning of the Court. Though the instance has since become a thing of the past, it is still etched in public memory.

The judiciary needs men and women of steel. It needs a heart that throbs for the masses, not for the ruler. The collegium system was introduced with that goal in mind. But, then, the men behind the machine failed it. Unfortunately, it is the consumer of justice who suffers. The post-retirement positions offered by governments have proved to be another tool to control or mould the judiciary. The deity of justice was blind folded, telling the justice-seekers that before it, there is no distinction between the rich and the poor, the powerful and the weak, the ruler and the ruled; and for all of them, the scales of justice are even. Now it has its eyes open; the blind fold has been removed.

The judiciary needs men and women who remain true to their office and the Constitution. Press conferences by judges couldn’t restore the ideal. It is time for the consumer of justice to raise the banner. That idol of justice, made of clay or stone, has to have a heart that beats. It must move and act.

The writer is a former judge of the Delhi High Court