The Supreme Court’s “basic structure doctrine” recently completed its 50th year. On April 24, 1973, in the landmark Kesavananda Bharati v Union of India, a 13-judge bench of the Supreme Court invented the doctrine that mandates the court to review and restrict Parliament’s power to amend the Constitution’s fundamental principles. But a key fallout of this ruling, something that is borne out by the events that followed it, was the executive’s interference in the appointment of judges — something that has shaped Indian judiciary over the last five decades.

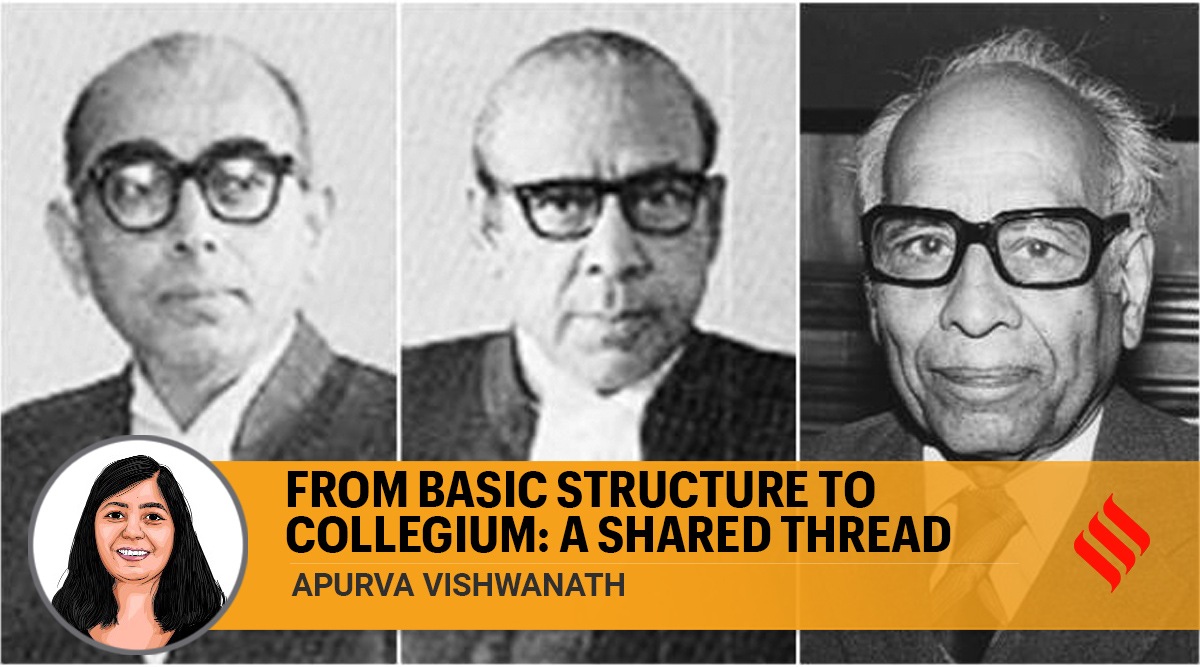

The Kesavananda ruling was delivered a day before then Chief Justice Sarva Mitra Sikri was due to retire on April 25, 1973. Stitching together a narrow majority of 7-6, CJI Sirki led the majority while Justice A N Ray led the minority judges.

On April 26, 1973, breaking the convention of seniority, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi appointed Justice A N Ray as Chief Justice of India. This meant that three judges who were in line before him — J M Sheelat, K S Hegde and A N Grover — were superseded. The three judges immediately went on leave and subsequently resigned from their offices.

Congress leader Mohan Kumaramangalam was reported to have said that the government did not want to appoint Sikri. “But that time our plate was too full because of the dispute over the crisis within the Congress party,” he said, according to Gadbois.

During CJI Sikri’s tenure, there was also an effort to pack the court for the Kesavananda ruling. There were nine new appointments that occurred over a period of just 15 months from July 1971 to October 1972. Justice Jaganmohan Reddy, one of the 13 judges on the Kesavananda bench wrote in his book, We Have a Republic, that of the nine appointed during Sikri’s tenure, only one was his nominee — Justice H R Khanna (who was part of the majority bench). Of the nine appointees, seven were on the bench in Kesavananda — Justices D G Palekar, H R Khanna, K K Mathew, A K Mukherjea, M H Beg, S N Dwivedi and Y V Chandrachud. Except for Justices Khanna and Mukherjea, the others decided in favour of the government.

“The days of the CJI surveying the High Court landscape, deciding who to bring to Delhi and seeing the government announce the appointment ended in 1971,” Gadbois wrote of the Sikri Court.

In Parliament, it was Mohan Kumaramangalam, the Minister of Steel and Mines, and not Law Minister H R Gokhale who defended the appointment of Justice Ray as CJI. He said that the supersession had to be considered within the context of confrontation between the government and the Supreme Court since 1967, when the government faced a string of setbacks in the Bank Nationalisation case, Privy Purses case and ultimately, in the Kesavananda ruling.

“We have to take into consideration… His basic outlook, his attitude to life, his politics – not to the party to which he belongs, but what it is, that makes the man – through which spectacles he looks at the problems of India,” he said.

If not for the supersession, Ray would have not been the CJI who carried through the Emergency. Justice H R Khanna was next in line to be appointed CJI with a five-month tenure. Popularly referred to as the second supersession, in 1977, Gandhi broke the seniority convention again, announcing hours before Ray’s retirement that Justice M H Beg would be appointed CJI. In the Kesavanada ruling, both Ray and Beg had decided in favour of the government.

Post Emergency, when Indira Gandhi returned to power, then Law Minister Shiv Shankar issued an order on March 18, 1981 seeking to transfer one-third judges of High Courts to “further national integration”. The challenge to this move became the First Judges case as it is popularly known. In S P Gupta v Union of India, the Supreme Court decided in favour of the government, holding that the concept of primacy of the Chief Justice of India was not really to be found in the Constitution.

Twelve years later, in what is known as the Second Judges case, in 1993, the Supreme Court overturned this decision and cemented the collegium system of appointment of judges which is still in place. The SC held that the questions of appointments had to be considered “in the context of the independence of the judiciary, as a part of the basic structure of the Constitution, to secure the ‘rule of law’ essential for the preservation of the democratic system, the broad scheme of separation of powers adopted in the Constitution, together with the directive principle of ‘separation of judiciary from executive…’.”

In 2015, it was Kesavananda’s basic structure doctrine that the Supreme Court used for the first time to fully strike down a constitutional amendment to alter the process of appointment of judges. The 99th Constitution Amendment Act, commonly called the NJAC Act, gave the executive a foot in the door on judges’ appointment.

Today, much of the criticism of the basic structure doctrine is that unelected judges decide what aspects of the Constitution must be protected, especially when their appointments are made by themselves. While both these issues might be up for challenge in the future once again, one must acknowledge that the histories of the doctrine and how the unelected judges are appointed are entwined.