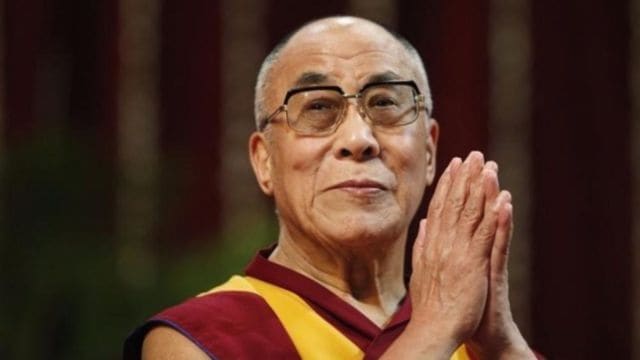

At the 15th Tibetan Religious Conference that began today in Dharamshala, the 14th Dalai Lama affirmed the continuation of his institutional reincarnation. Leaders of the principal Tibetan sects are attending the conference, which ends on July 4. In the weeks leading up to the announcement, there had been considerable speculation surrounding his next reincarnation. The Dalai Lama, who turns 90 on July 7, had confidently stated in his latest publication that his successor could emerge outside the borders of China.

The Dalai Lama’s reincarnation is a profound event rooted in a 15th century story about a boy who recalled his past life as Gedun Drub, a key figure and the First Dalai Lama in the Gelugpa tradition.

Drub’s spirit reemerged in 1475 with Gedun Gyatso, who possessed the extraordinary ability to recall his previous lives. After his death, he was honored as the Second Dalai Lama. The legacy continued with Sonam Gyatso, born in 1643, who received the title “Dalai”, meaning “ocean”, from Mongolian leader Altan Khan in 1578, signifying the all-pervasive ruler of Inner Asia.

Yonten Gyatso, born in 1589 as a descendant of Altan Khan, was chosen as the Fourth Dalai Lama. Yonten’s successor, Lobsang Gyatso, born in 1617, was recognised as the Fifth by the Third Panchen Lama who formed a powerful alliance with Mongol Gushi Khan, and their partnership was key in establishing the Ganden Phodrang regime at the Potala Palace in 1642, shaping the future of Tibetan governance under the Dalai Lama.

In the 17th century, Chinese Emperors Kangxi and Qianlong adopted the Mongol-style patronage of Tibetan Lamas, incorporating the Dalai Lama and the Panchen Lama as secular authorities within their imperial framework. This strategic alliance strengthened their control over Tibet and lasted until the Qing dynasty’s fall in 1912.

Beijing asserted that the Fifth Dalai Lama established a significant tributary relationship with the imperial court after paying homage to Emperor Shunzhi in 1653. He presented the emperor with exquisite horses and precious gems, and in return, received a golden seal and the prestigious title of “Overseer of the Buddhist Faith on Earth Under the Great Benevolent Self-subsisting Buddha of the Western Paradise”. This exchange solidified the Dalai Lama’s authority and legitimacy as a spiritual leader.

Tsangyang Gyatso, born in Tawang in 1680, was acknowledged as the Sixth Dalai Lama by the Panchen Lama and Mongol leaders. His legitimacy faced opposition from competing Mongol warlords, and he was ultimately assassinated while traveling to Peking to meet with Emperor Kangxi.

The Seventh Dalai Lama, Kelsang Gyatso, who was born in 1708, received his consecration from the Panchen Lama with the backing of the Qianlong Emperor.

Jamphel Gyatso, who was born in 1758, was also appointed by the Sixth Panchen as the Eighth Dalai Lama. This significant legacy faced challenges after the Nepali invasion of Tibet in 1791, during which Emperor Qianlong modified Tibet’s internal autonomy while implementing the “Twenty-Nine Article Imperial Ordinance”. This ordinance replaced the Regent system with the Kashag (Council) for governance. Additionally, the Golden Urn method for selecting the Dalai Lama and other notable Lamas was established by Qianlong.

The immediate Ninth Dalai Lama, Lungtok Gyatso, born in 1805, could bypass the Golden Urn process due to Qianlong’s abdication in 1795. Tragically, Lungtok died at the age of nine in 1815.

The selection of Jampel Tsultrim Gyatso, born in 1816, as the 10th Dalai Lama was also confirmed through the Golden Urn ceremony. He received novice ordination from the Seventh Panchen. He, too, passed away young in 1837. These events underscore the challenges faced by Tibetan leadership during this tumultuous era.

The 11th, who was born in 1838, was also selected via the Golden Urn process; however, his life was sadly abbreviated in 1856 following his ordination by the Panchen Lama. The 12th Dalai Lama, selected in 1858 via the same method, prohibited European entry into Tibet and died at just 20.

Thupten Gyatso, the “Great Thirteenth”, was an important figure. It is believed that the Tibetan Nechung oracle and the Eighth Panchen Lama significantly contributed to his selection, which was subsequently endorsed by the Guangxu Emperor in 1879.

The 13th was a prominent nationalist who spent time in exile across China, India, and Mongolia. His administration was responsible for the signing of the 1890 Anglo-Chinese Convention concerning the Sikkim-Tibet border, despite Lord Curzon’s objections to his covert alliance with Tsarist Russia.

In 1904, during Francis Younghusband’s mission to Lhasa, he sought asylum in Mongolia but returned to Lhasa after Britain and Russia finalised the Convention pledging not to interfere in Tibet in 1907. He traveled through Peking (Beijing), where he established a strong relationship with Dowager Empress Cixi.

As Thupten Gyatso endeavoured to consolidate power, the Manchu military suppressed his assertions of autonomy. Following the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1911, he traveled to India in search of military support, which the British refused to provide. Upon his return to Tibet in February 1913, Thupten audaciously proclaimed Tibet’s independence, a declaration that was acknowledged solely by the theocratic government of Mongolia.

The present 14th Dalai Lama, who was born in 1935, was identified through profound spiritual methods. The Kuomintang (KMT) administration’s claim that General Wu Zhongxin was responsible for confirming the 14th Dalai Lama in 1940 was strongly disputed by the Tibetans. Interestingly, Basil Gould, the British representative in Gyantse, attended the enthronement ceremony in Lhasa alongside the Sikkimese envoy Chogyal Pipon Sonam Wangyal, although their seating arrangements were not clearly defined.

There is no available reference point regarding India’s role in the history of Tibetan succession; rather, the relationship between India and Gaden Phodrang was characterised by hostility. For instance, during the era of the Fifth Dalai Lama, the Tibetans initiated a series of assaults on Bhutan, Ladakh, and Monyul (Tawang). The attack on Ladakh in 1679 resulted in a four-year military standoff, which concluded when the Mughal Empire intervened to safeguard the borders of Ladakh. Consequently, Tibet managed to seize half of Ladakh, including Burang, Guge, and Rudok.

During the reign of the 11th Dalai Lama, Kalon Tsaidan Dorje and Dapon Spel Bzhi, along with their forces, ruthlessly killed the Dogra soldiers and decapitated General Zorawar Singh in 1841 at Taklakot.

The 13th maintained a cordial relationship with India and sought assistance in opposition to China. He judiciously agreed to adhere to the 1914 Simla Convention; however, his officials subsequently reversed their position.

The 14th Dalai Lama did not take office until 1951; however, his regent dispatched wireless telegrams to Jawaharlal Nehru in October 1947, asking for the return of “Tibetan territories,” which encompass around 300,000 square kilometres (more than ten percent) of Indian land. After arriving in India in 1959, he distanced himself from these telegrams.

While China labels the Dalai Lama as a “political exile”, India regards him as a “revered spiritual leader”, permitting him to continue his religious endeavours.

It remains uncertain if India possesses the historical basis and legal structure necessary to validate the reincarnation. A significant portion of this issue is intertwined with the tension between imperialist China and communist China. Ideally, the authority to decide should lie with the Tibetans, as the evidence indicates that the Panchen Lama consistently played a crucial role in the reincarnation of the Dalai Lama.

The writer is an expert on Himalayan Affairs