Mention Imtiaz Ali’s forthcoming film Chamkila and chances are that you think of Diljit Dosanjh, the singer-actor who is the hero of this film.

But in Punjab, the name Chamkila is a sobering reminder of a dark decade. It transports you to 1988, a year marked by the ominous reign of militants in the state.

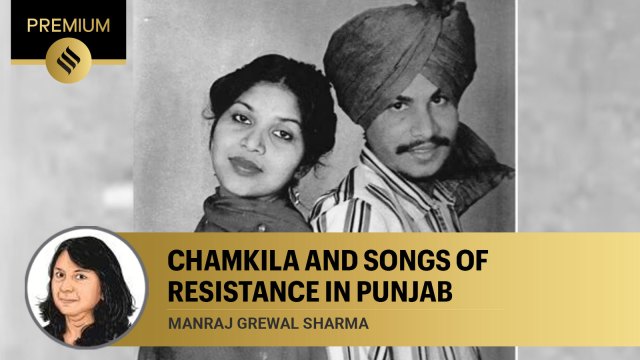

Amar Singh Chamkila, arguably the first superstar of Punjabi pop — it’s said he was booked for over 400 programmes in a year — was shot dead by militants along with his wife and co-singer Amarjot Kaur at Mehsampur near Jalandhar in March 1988. He was all of 27.

Those weren’t good times for poets, writers, singers and dreamers. Prof Jagrup Sekhon, co-author of Terrorism in Punjab: Understanding Grassroots Reality, recounts how, in April 1987, militants had laid down a 13-point code called Samaj Sudhar Lehar, putting down rules for how people should dress, interact and even marry. The boisterous Punjabi baraat was reduced to just 11 people and lehenga was a no-no for brides who were told to stick to salwar-kameez.

The year 1988 began on a bloody note with the killing of Jaimal Singh Padda, 45, a Naxal poet, singer and peasant leader. Paramjit Judge, author of Religion, Identity and Nationhood: The Sikh Militant Movement, remembers interviewing Padda in 1981 for his thesis on Naxals. “He was a simple man who lived an austere life in two rooms.”

Padda’s work inspired filmmaker Anand Patwardhan to make a documentary on Punjab Communists with the title borrowed from a popular Padda song, “Ona Mitran Di Yaad Pyaari” (In sweet memory of those comrades).

Padda, who coined the slogan “Na Hindu raj, na Khalistan, raj karega mazdoor kisan (No Hindu state, no Khalistan — it’s the working class that will rule)”, was gunned down by militants of the Khalistan Commando Force (KCF) outside his house in Lakhan Ka Padda village near Kapurthala on March 18, 1988.

Five days later, militants shot down Pash, 37, one of the most celebrated Punjabi poets. Born Avtar Singh Sandhu to an Army officer, Major Sohan Singh, Pash began writing poetry at the age of 15. Greatly influenced by the Naxal movement and Bhagat Singh, he was 18 when he published his first book of revolutionary poems, Loh-Katha (Iron Tale), in 1970.

The state, in a bid to silence him, arrested him on trumped up charges of murder, of which he was acquitted after two years in prison.

Prof Chaman Lal, who translated Loh Katha into Hindi — he won a Sahit Akademi award for it — says Pash openly raised his voice against militants. Working as a schoolteacher in a village next to his native Talwandi Salem near Nakodar, Pash started publishing a wallpaper called Deewar in which he would quote verses from Sikh gurus to show how the movement was antithetical to the principles of Sikhism. Warned by friends and family about the imminent threat from militants, he moved to the US in 1986, where he continued penning the wallpaper and pamphlets decrying militancy.

In 1988, he had returned to India to get his visa renewed when he was shot dead at the village well on March 23, the death anniversary of Bhagat Singh. He was to leave for the US the next day. “Death couldn’t silence Pash; his influence has only grown, and he is one of the most translated poets of India,” says Chaman Lal.

Despite the diktat of militants, Chamkila’s popularity continued to grow. Prof Judge, who is penning a book on Punjabi singers, says Chamkila, a Ramdasiya who wrote his songs himself, used to sing on three subjects — the valour of Sikh gurus, the plight of the poor, and illegitimate relations. “He was just holding a mirror to society when he sang about the male gaze or desire but he was called a ‘lecherous’ singer. Militants had given a diktat against what they called ‘vulgar’ songs and most singers complied.”

It was a chilly day in March when Chamkila and Amarjot were killed in a hail of bullets at Mehsampur village near Jalandhar. “There are many theories about his death, one is that he was killed for marrying a Jat woman despite being a Dalit, another was that he was eliminated by other Punjabi singers who were jealous of his popularity. But the predominant theory was that the couple fell to militants. Those days, it was easy to blame any killing on militants,” says Judge.

Another killing that rocked the entertainment world was that of Veerendar Singh, the superstar of Punjabi cinema and a cousin of popular Bollywood star Dharmendra. The 40-year-old was shot dead while he was filming Jatt te Zameen in Ludhiana in December 1988. His death remains shrouded in mystery but back then, militants were blamed.

Chaman Lal, who was then teaching Hindi at Punjabi University, Patiala, says such was the fear of the gun that diktats by militants were followed even by eminent vice-chancellors. At Punjabi University, all notice boards were painted saffron and press releases by militants were posted prominently. But clearly not satisfied, the militants shot down Dr Ravinder Ravi, a well-known Punjabi author and president of the university teachers’ association, at his home in May 1989. An open critic of violence, Ravi was the first PhD scholar of the varsity.

The targeting of writers and scholars had begun much earlier, though. It was in February 1984 that Sumeet Singh aka Shammi, 30, the editor of Preetlari, a highly respected left-of-centre literary journal which preached Hindu-Sikh unity, was shot dead by militants.

Madan Lal Didi, his father-in-law and general secretary of the Punjab unit of the All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC), later said that Shammi had paid the price for his boldness in criticising the terrorists despite repeated threats.

But these killing failed to silence the voices of peace and sanity. Poets, writers and playwrights continued to pen their agony, targeting both the militants and the state repression that followed.

As Manjit Tiwana, a Sahitya Akademi award winner, wrote:

What times are these,

Sitting on the threshold of it,

We ask the whereabouts of our home.