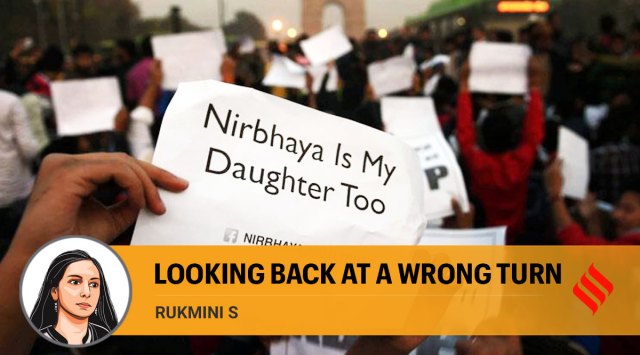

You’d be hard-pressed to find a young woman who lived in Delhi at the time who will ever forget the December of 2012. The sheer shock and horror of reading and hearing about the violent assault on a young woman, the palpable sense that a dam had broken and that a long-suppressed discussion was spilling into the public sphere, the days and nights of street protests, and ultimately the hope that some things were finally going to change for good. I was one of them. Ten years on, as I take stock of the data, I try to recall what that late 2012 hope felt like, and whether it has been met.

First things first. The heightened media and public conversation after the Delhi assault did result in higher rates of reported crimes against women, an increase that women’s rights activists say suggests better reporting rather than more crime. The post-2012 activism does appear to have resulted in a sharp increase in police-recorded sexual crime, sexual molestation in particular, that has since levelled off. The police disposal of such cases has kept up. Despite a sharp increase in reported cases, pendency at the police level did not increase substantially. However, the rate of convictions in court has not gone up substantially.

Why is this? This would require us to look beyond police statistics, at other sources of data that paint a more nuanced picture of what sexual violence in India looks like — a picture that is more complex, more complicated and more surprising than what the narrative that took hold in the last decade would suggest.

For months after the Delhi assault, the media remained relentlessly focused on cases like the Delhi assault which involved “stranger” rape — cases where a person unknown to the woman assaults her. Even now, such cases dominate media discourse and, as a result, public imagination. Such cases made up 3.5 per cent of reported assaults in 2021 (as per the police statistics from the National Crime Records Bureau) and 0.5 per cent of experienced assaults in 2019-21 (as per household-level questioning from the NFHS).

When the conversation did move on to discussing intimate partner violence, it was based on faulty and misleading data that ultimately resulted in misguided and damaging legal changes. In the months after December 2012, there was widespread media outcry over trial court judges giving short sentences to accused men who appeared to have married their victims. But while analysing court cases involving alleged sexual assault in Delhi, Mumbai and Madhya Pradesh, I found that the largest share of cases tried by courts involved consenting relationships, often inter-caste and inter-religious, of which families disapproved, that were resulting in false charges of kidnapping and rape. Such cases overwhelmingly resulted in acquittals or in short sentences.

Others have found similarly. An analysis by Enfold Proactive Health Trust of 1,715 “romantic” cases under the POCSO Act decided between 2016-2020 by special courts in Assam, Maharashtra, and West Bengal revealed that such cases constituted 24.3 per cent of the total cases decided by courts. Parents and relatives of the girls constituted 80.2 per cent of the complainants; acquittals were recorded in 93.8 per cent of the cases. An analysis by Vidhi Legal Centre of 138 POCSO judgements found that romantic relationships between minors formed a substantial share, and most resulted in acquittals.

Despite this mounting evidence, some of the misguided turns that legal reform took post-2012 have not been reversed. These included the raising of the age of consent for women from 16 to 18, and the institution of mandatory minimum sentencing norms that remove the discretionary powers that allowed judges to halt such miscarriages of justice.

So where does this leave us? Is India any different from other countries in terms of sexual violence or was the blinding spotlight that it found itself in for the last decade unwarranted?

In terms of sexual violence reported to the police, proportionate to the female population, India is roughly in the middle of countries around the world, comparisons between India’s national crime statistics and the Unietd Nations Office of Drug and Crime statistics show.

What sets India apart are two rarely discussed indicators which emerge not from police recorded statistics, but from internationally comparable demographic and health surveys that ask women about the violence they actually experience. One, while intimate partner violence forms the bulk of sexual violence the world over, the sheer scale of sexual violence experienced within the marriage in India separates it from most of the world. Consequently, the share of sexual violence that women experience at the hands of strangers is lower than almost anywhere else in the world. This is not entirely unexpected. Marriage is near universal in India, meaning that vast majority of experiences including sexual experiences and intimate partner violence take place within the marriage in India.

The other indicator that sets India apart is particularly worrying. The share of Indian women who experienced violence but did not tell anyone about it is among the highest when compared to other countries. This includes not just women who did not report this violence to the police, but also those who did not tell any friends or family about it — they suffered alone and in silence.

Ten years after the Delhi assault, this is a terrible legacy for Indian women to be living with. What it points to is that the conversations needed to substantively support women and specifically support them if and when they experience sexual violence have not yet happened. Instead, some of the loudest discussions were those unsupported by data.

The tragedy of December 2012 opened up space for a long overdue conversation about the safety of women in India. We must ensure it isn’t squandered by a misreading of the data.

The writer is an independent data journalist. Ramakrishnan Srinivasan contributed to the data analysis