Click here to follow Screen Digital on YouTube and stay updated with the latest from the world of cinema.

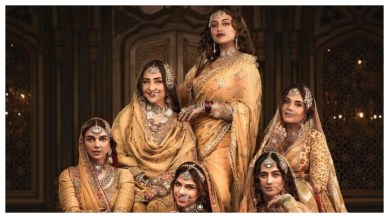

The Sanjay Leela Bhansali school of filmmaking is all about maximalism, which has beautiful actresses wearing the most intricate jewellery and costumes. And over the years, Bhansali’s fans have celebrated this aspect of his movies a little too much. Not just this, fans have also found a way to appreciate the women in Bhansali’s world. These women who look stunning in every frame are more than their looks and we are told that they are to be compared to ‘devis’ but the way Bhansali treats them in Heeramandi, it seems unlikely.

In Heeramandi, Bhansali’s first web series on Netflix, we are introduced to women who work as ‘tawaifs (courtesans)’. For the unversed, ‘tawaifs’ are the women who put up an elegant show of song and dance, with a touch of seduction, and being a regular visitor at their ‘kothas’ is somehow seen as a status symbol for the ‘nawabs’. They aren’t mistresses, and they aren’t lovers, they teach the art of lovemaking but it’s not seen as a transactional affair.

One would assume that a woman who lives in this era, working as a ‘tawaif’ is living a rather difficult life, but Bhansali repeatedly asserts throughout the show that the ‘tawaifs’ are ‘lahore ki raniyan’. One of the characters says that the ‘tawaifs’ have immense power, and are the actual decision makers behind the ‘nawabs’, but that is far from the truth in the show’s world.

Also read – Heeramandi: Sanjay Leela Bhansali glamourises the suffering of women and aestheticises their pain

The tawaif-to-be Alamzeb has no interest in following in her mother’s footsteps, but in a world where the women apparently hold all the cards, we learn that it isn’t all women but just Mallikajaan who has the power to make decisions, and that too, only over her minions. Mallikajaan decides when the most popular ‘tawaif’ of her ‘kotha’ must retire, and she holds the final say when two ‘tawaifs’ are quarreling over the same man. This isn’t a world where women have power, this is a dysfunctional society where a woman has declared herself as the authoritarian, and everyone in her orbit is just trying to branch out and rebel in their own way. But outside of ‘Shahi Mahal’, these women have no power, not even Mallikajaan. The ‘nawabs’ can choose to boycott them at their will, and so they do. The cops can rape them, and there is absolutely nothing they can do about it.

Bhansali, true to his style, chooses to focus on song-and-dance, jewellery and costumes that will end up on Pinterest boards of brides-to-be, and dialoguebaazi, and not the actual lack of power these women have. It may appear as though these women are being celebrated but they are treated like sacrificial lambs who are made to believe that their sacrifices have some kind of meaning. The worst example of this comes across in a scene where a woman submits to gang rape, after she herself suggests it, and gives a monologue about ‘sacrificing herself for greater good’. Another character ‘sacrifices’ herself, to save her friend from the ‘tawaif’ market, and here too the ‘sacrifice’ requires her to have non-consensual sex. Bhansali makes the idea of ‘sacrifice’ appear noble, without actually inspecting how these women are being tortured over and over again, and never reaching any point of salvation.

There was a time in Indian cinema, when female characters were portrayed as ‘bechari abhla naaris’. The female characters in the alpha-male movies existed as wives or sisters or mothers, and were there only to serve the men of the story. They were repeatedly taught to sacrifice themselves for their family, and society but then we moved forward. Female characters started getting independent, having more agency and were not just seen from the lens of the male characters of the story, and as audience, we loved that change. Much like the women, men too started evolving in the movies but now it’s starting to feel like the clock is turning back. The Pushpas, KGFs and the Animals of the last few years have brought back the alpha-man and Heeramandi has brought back the sacrificing woman, which isn’t a cause for celebration.

ALSO READ | Heeramandi and beyond, Sanjay Leela Bhansali and his stories of love, loss, and longing

Heeramandi is set against the backdrop of the freedom struggle, which only comes to the forefront in the last two episodes, and it seems almost like an afterthought when Mallikajaan too becomes a part of the rebellion. Until this point in the story, women are quarreling with each other over property and men. And the abrupt awakening where they decide to let go of all their differences feels like a cop out.

Heeramandi is set in the 1940s and belongs to a time when ‘tawaifs’ actually had a role in society. For good reason, that role doesn’t exist anymore, and perhaps its time that we stop celebrating a culture that was anti-feminist to begin with.

Click here to follow Screen Digital on YouTube and stay updated with the latest from the world of cinema.