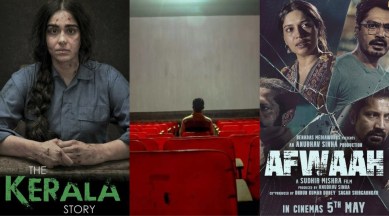

On May 10, five days after the controversial film The Kerala Story and Sudhir Mishra’s drama thriller Afwaah released on the same Friday, filmmaker Anurag Kashyap came out against the move of banning the former, writing that one can disagree with a film, find it a “propaganda”, but halting its screening is wrong. Instead, he asked people to watch Afwaah and make their voice “stronger”. His statement was appreciated, his larger point understood, but there was one common complaint: How to watch the film, when it’s playing virtually nowhere?

The Friday of May 5th, when the two polar-opposite films released, witnessed significant drama and disappointment. While The Kerala Story–declared tax free in Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh–dominated news cycle over the weekend with its unending controversies and ever-growing box office collections, Afwaah battled a silent heartbreak even as reviews championed it as one of the bravest films of the year.

Glowing reviews, undignified release and OTT

The Sudhir Mishra directorial, produced by Anubhav Sinha and Bhushan Kumar’s T-Series, opened in merely 60 screens across India, a shockingly low number for a film headlined by actors Nawazuddin Siddiqui and Bhumi Pednekar — popular names among the multiplex and single screen audiences. The Kerala Story, led by relatively less-known Adah Sharma, released in 1276 screens and reached almost 1500 screens by Monday. The film found support from the BJP government, while Afwaah vanished on the opening day itself.

The film’s collections, according to trade sources indianexpress.com spoke to, were negligible to even report. The Kerala Story, meanwhile, is expected to end its lifetime box office run with collections north of Rs 225 cr. According to a source close to the film, Afwaah got an “undignified” release, being not even accorded a fighting chance at the box office to translate its glowing reviews to respectable box office collection.

“The film wasn’t given its due at all. Understood that it is a niche film, but to open it in less than 60 screens is just terrible. On top of that, the show timings were a joke — early morning, one odd in the afternoon or late at night. The film has to be available to the public for them to access it,” the source said.

When indianexpress.com reached out to Sudhir Mishra over the claims of Afwaah being given an undignified release, the filmmaker said he would have also liked for more people to access the film on the big screen, but today, the scenario is such that smaller films will release theatrically only as a precursor to their OTT debut, which is where the makers hope their audience finally watches the film.

“Ultimately it’s going to come on OTT and smaller, more independent films are released as a precursor to whoever wants to see it and some people might see it. The press can see it and it can create environment for the film. Obviously, I would like more people to see it in theatres. A lot of people have told me and I keep seeing on my timeline that people have written, ‘Where can I see it?’ I keep saying, ‘On OTT,'” Mishra said.

Story continues below this ad

The move of theatrical-first, sources say, is because streaming platforms no longer buy films direct-to-OTT, as was the case during the pandemic. A film now has to open in minimum 25 screens to qualify for a post theatrical OTT debut. Mishra said he is aware a sizeable audience did miss out watching Afwaah on the big screen, but post-pandemic theatrical isn’t an easy task to pull off.

“I know everybody likes to watch movies in theatres, but theatrical is another monster all together… Because the real estate, the prices, the cost of release is really not in my hands at all,” he added.

A marketing source told indianexpress.com that OTT platforms are restructuring their strategy, realising that they can’t be a “dumping” ground for makers, who are sure their films won’t do box office magic.

“OTT platforms are reluctant to buy films for direct release. Filmmakers are expected to promote their films, release them in theatres in order for the platforms to buy them. To make this possible, many filmmakers, who’re recently releasing small films in theatres, are opting to release their films in about 100 screen all over India for over a weekend. They then make release proposals to OTT platforms and a release plan comes through,” the source said.

Missing Stars

Story continues below this ad

While film strategy and post-release acquisition happens behind closed doors, the ones who end up facing the brunt of a flop are actors– and they aren’t happy. According to sources, the actors associated with Afwaah knew that the film was likely to have a muted release, prompting them to hold themselves back from putting their name and face to the film’s promotions, as, “without any fault of theirs”, the tag of flop would come on them.

“There is no doubt that they signed the film because it was good, because they believed in it. They did their job as actors; now shouldn’t the makers give it some credible release? A dignified release is all that was needed.”

Something similar was observed during the promotional campaign of Sinha’s Bheed, starring Rajkummar Rao and Pednekar. After the initial few media rounds, the actors weren’t seen promoting the film. “And they aren’t wrong at all. The blame would come on them. A few things need to be changed. Sure, smaller films post pandemic have been severely affected, but, again, give it a chance? Especially when you know you have a good film in hand,” the source said.

Why blame the producer?

Story continues below this ad

There could be internal discussions about for-the-sake-of-it release of Afwaah, but trade sources also note that a film’s release plan is carefully drawn by the makers after studying the market. If Afwaah, a socio-political drama released in under 60 screens, there was a good reason for it.

“It is a clear case of demand and supply. The Kerala Story opened in 1200 screens, reached 1500 count in four days. Its second week screen count is higher than its first. It shows that there was an audience waiting for it, ready to pay and watch. The producers sensed it, increased the shows. If Afwaah was that keenly awaited or if it genuinely had any major on-ground interest, its shows would have increased too.

“A producer will try to minimize their losses. The only way to do it is to control the release, because a theatrical release is expensive. There is no point overexposing your film by giving it a wider release, which would burden it further,” trade source said.

The next release after The Kerala Story and Afwaah was actor Vidyut Jammwal’s spy actioner IB 71. Neither a niche film like Afwaah, nor the one to benefit from any government backing, IB 71 was released in approximately 800-1000 screens and managed to put up a respectable figure of Rs 8.43 cr in four days.

Films of our times

Story continues below this ad

In his tweet, Kashyap best described Afwaah as a film that “talks against misuse of social media and how inherent prejudice is weaponised to create hatred and unrest.” Contrary to this, The Kerala Story was dubbed by many as hate speech masquerading as a film. The Kerala Story claimed to tell stories of more than 32,000 Kerala women who’d allegedly been radicalised by Islamic fundamentalists, only to later backtrack and change the number to “three” after backlash and allegations of disinformation.

The Kerala Story, much like last year’s The Kashmir Files, received support from the ruling BJP government, with even Prime Minister Narendra Modi citing the film in his speech. While the two films have clearly shown the industry the numbers that can be achieved if the ruling government blesses a film — even without an A-list cast or acclaimed director — trade sources said one has to “wait and watch” to see how many of such projects get bankrolled.

But Mishra, whose Afwaah was a strongly political film, is at least happy that he could mount a film like this in today’s times, its box office fate notwithstanding. “You will agree I had a lot of balls making the film. Uske aage main kya kar sakta hun? In the time of this and that, I have put my head into something and made a film to also to prove to the younger lot that you can do what you want to do. We all have to keep trying.

“We have to stand up to be counted. We do that by making a film. Our body of work reflects that, wherever they watch it now, in theatres or OTT. The film is a precursor to a debate, we can have conversations. Whether people like it or not, at least it will provoke people and start a conversation. To some extent, it already has,” he concluded.