Poetry in percussion

From kings’ courts, concert halls to your mohalla stage, why the tabla is everywhere

Standing on the shoulders of the generations before him, Ustad Zakir Hussain took the tabla to new heights, his fingers drumming, thumping, flitting, playing and flying on the instrument, coaxing it to release sounds in ways unheard of earlier.

Exactly a month ago, on December 15, 2024, Hussain breathed his last.

The musician and the instrument made for a harmonious pair — both charismatic, layered, aware of the weight of history on them and open to the future.

The tabla is among the youngest instruments in Hindustani or North Indian music. Having mutated from some of the earliest musical instruments known to humans, its versatility made it indispensable to kings' courts and courtesans' stages, rarified concert halls and the humblest folk performances. Yet, for long, the tabla was the side act, one part of the lead performer's accompaniments. It is relatively recently that it has taken centre-stage. Here is the story of its evolution, and what it says about Indian music.

From tabl to tabla

Instruments like the tabla are said to have been in use in India for thousands of years. The 2nd-century rock-cut Bhaja caves in Maharashtra have a carving of a woman playing a set of drums that resemble the tabla.

Referencing Natya Shastra, the ancient Sanskrit text attributed to sage Bharata around 200 BCE, The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, says, “Only in the drum chapter (chapter 33) do we find a comprehensive exposition of instrument-making and performance techniques...The fact that abstract principles of rhythm and meter and practical instructions in drumming appear in two separate chapters illustrates an understanding of their roles in Indian music.”

However, the instrument’s name has been derived from tabl, the Arabic word for percussion instruments. This etymology leads to the belief that Muslim rulers brought the tabla to North India.

Under the Muslim Sultanate and the Mughals, the popularity of the tabla grew in North India as the older dhrupad style of singing, which was more spiritual and devoted to Hindu gods, gave way to khayal singing, which has a larger variety of subjects. The instrument of choice for Dhrupad had been the pakhawaj, and in South India's Carnatic music, with fewer Muslim court influences, the mridangam, very similar to the pakhawaj, still rules.

In Carnatic music, the mridangam is used, which looks like a pakhavaj. Wikimedia Commons

In Carnatic music, the mridangam is used, which looks like a pakhavaj. Wikimedia Commons

“The pakhawaj is more majestic and sonorous, while the tabla is more shringarik (ornamental and stylish). This makes it better suited to khayal bandishes (fixed compositions), softer and melodic thumris, dance, folk music, etc.,” noted tabla player Anuradha Pal tells The Indian Express.

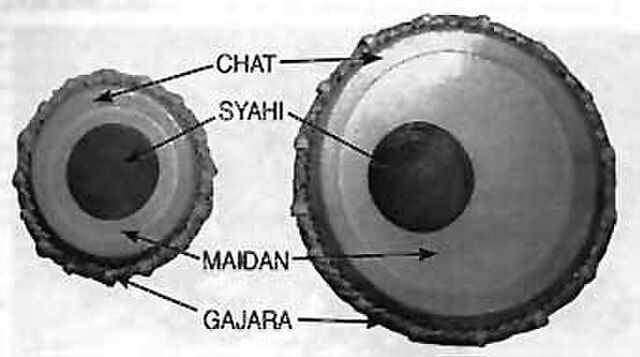

What sets the tabla apart from other percussion instruments is that it comes in a set of two — the bayan or the drum on the right, that produces the treble note, while the dayan, on the left, is for bass.

Widely used for the softer, simpler bhajans of the Bhakti movement, in Sufi music and as an accompaniment for Gurbani (hymns on teachings of Sikh gurus), the tabla truly prospered in the royal courts, which led to the development of six gharanas (schools with a distinct style) — Dilli (the oldest), Lucknow, Banaras, Ajrada, Farrukhabad and Punjab.

Anuradha Pal with Zakir Hussain, one of her gurus

Anuradha Pal with Zakir Hussain, one of her gurus

What makes the tabla sing

“The tabla is the most melodic, poetic drum,” says renowned tabla player Pandit Swapan Chaudhuri.

Unlike other drums, the notes of a tabla are more sustained — thanks to its unique build. The dayan, the smaller drum, is made of wood, while the bigger one is made of metal. Animal skin is stretched tight over the instrument’s hollow cavity. The skin is woven to the sides with leather straps, and the instrument is fixed with wooden guttas or dowels.

The drumhead consists of a syahi — the black circle in the centre — a mixture of powdered iron, coal dust and wheat or rice powder. When different parts of the drumhead or the syahi are struck, the air inside vibrates and produces distinctive sounds.

While high-end tablas are hand-made, cheaper versions are usually made by machines.

“Maestros like Zakir sahib usually have dedicated tabla makers working for them. For beginners, we sell tablas made by machines and assembled by us,” says Mohammad Hashim, who works at New Delhi’s decades-old Bina Musical Stores. “Goatskin is generally used for the drumhead. The younger the goat, the better. The skin of older animals is too tough for the delicate notes of the tabla. The dayan is made of sheesham, neem or tamarind wood, etc., while copper and brass are used for the bayan.”

Animal skin is the reason why musicians are always seen adjusting the instruments’ straps on stage. Anuradha Pal says, “Stage lights and the concert hall temperature often make the skin or the straps of the instrument to slacken, which makes the notes go haywire.”

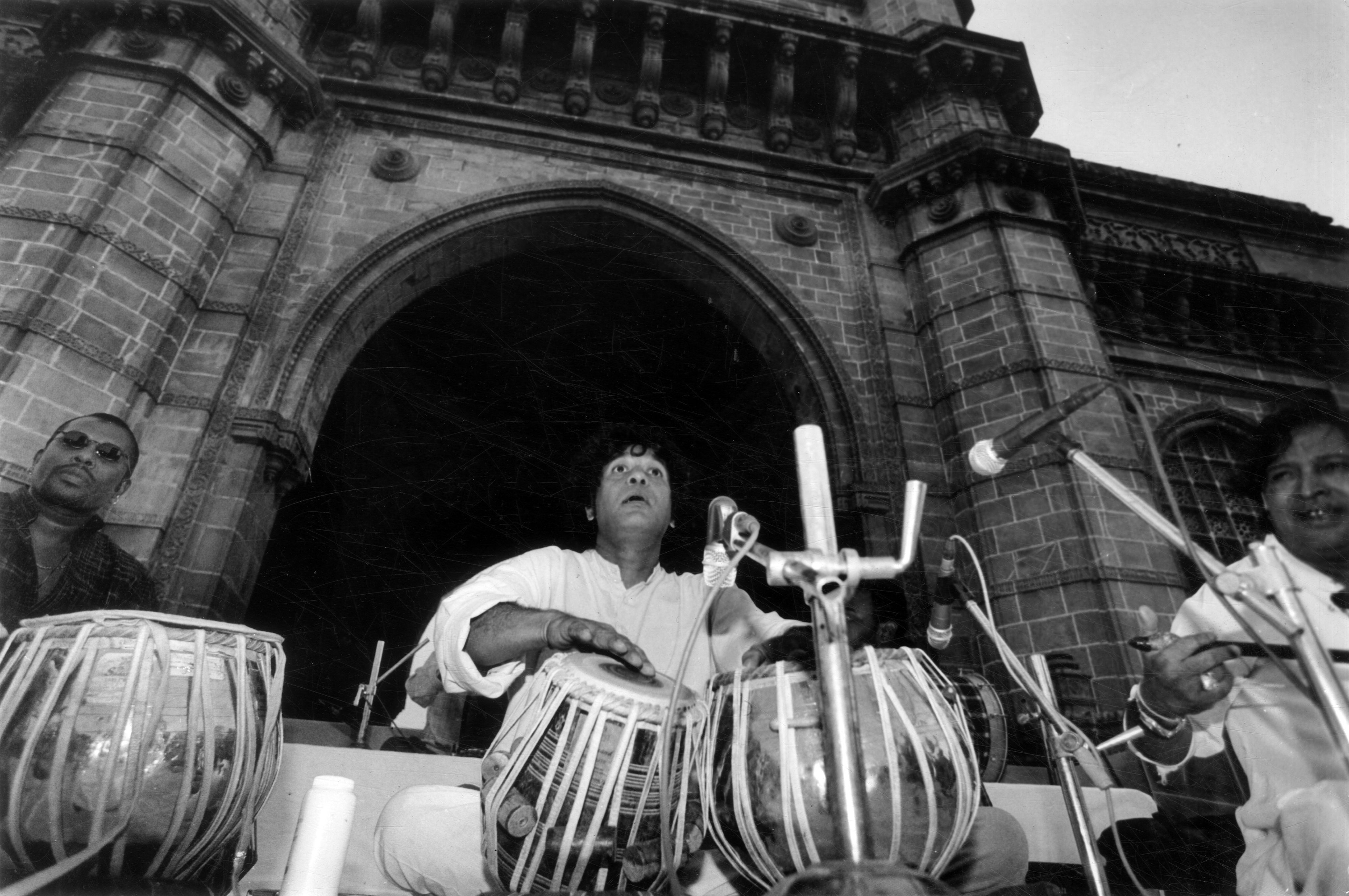

Zakir Hussain performs at the Gateway of India, Mumbai

Zakir Hussain performs at the Gateway of India, Mumbai

Social evolution

The Garland Encyclopedia, after talking about caste in India, says, “The social structure outlined above has penetrated all aspects of life, including music; perhaps one of its more unfortunate realities has been the relatively low social status afforded [to] professional male instrumentalists in the past, especially those playing instruments made of animal skin or gut...”; basically, instruments like the tabla.

As royal patronage declined and the British brought their Victorian sense of morality into India, the tabla attracted more stigma. From royal courts, it moved to the quarters of courtesans. “In centres like Lucknow, rigorous music was being practised in the courts of tawaifs. Until about 100 years ago, serious tabla players aspired to play with noted tawaifs, because of the learning opportunities and exposure this would bring them. However, for many, this brought the tabla disrepute,” Prabhakar Kumar Pandey, tabla teacher at Faridabad's Govt College for Women, said.

The fact that musicians were entirely devoted to their craft and limited to their community, with little interaction with the outside world, did not help in correcting perceptions. Music was passed along in families and gharanas, in the ustaad-shargid (teacher and disciple) tradition.

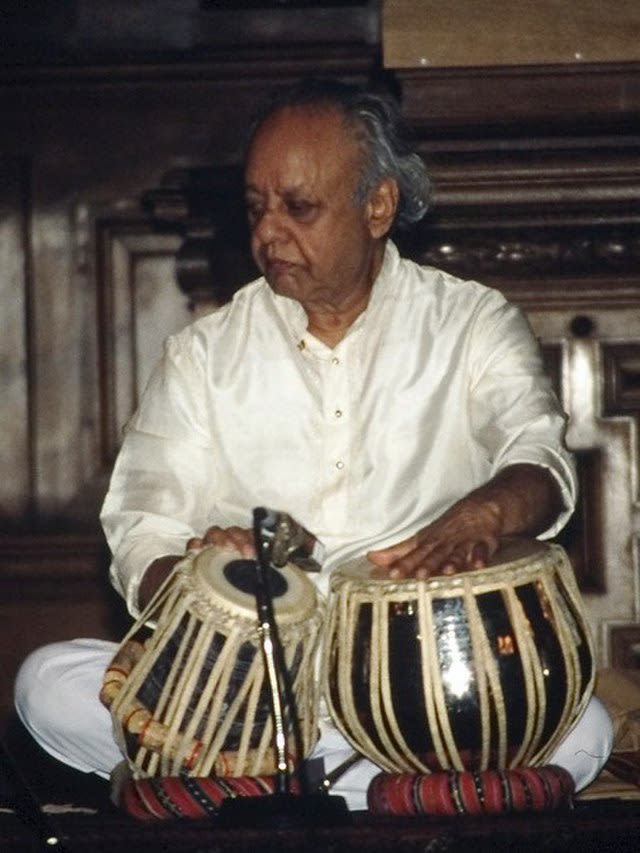

Ustad Allah Rakha Khan

Ustad Allah Rakha Khan

Zakir Hussain, in his biography, (Zakir Hussain: A Life in Music, by Nasreen Munni Kabir), alluded to the limits of this inward-looking world. “...musicians were socially unacceptable in the India of the 1950s and '60s... they were respected and asked to perform and so on, but they were very rarely invited into the homes of the higher echelons.”

He also said, “The social skills of Indian classical musicians of the past were limited. They spent 98 per cent of their time with their music. It would have been great if Abba [his father, the legendary Ustad Allah Rakha Khan] could have discussed politics, science or maths. But no, it was always music.”

He then goes on to mention that the late Sitar player Pandit Ravi Shankar was the only one who “could talk on any subject”. This is important, as Ravi Shankar was among the pioneers who transformed how Indian music was perceived.

Sitarist Pandit Ravi Shankar

Sitarist Pandit Ravi Shankar

Two things happened to change this perception. First, music moved out of ustad-shargid centres to colleges imparting formal education, where people from non-music families could also go. Second, well-educated, socially savvy musicians started coming to the limelight.

James Kippen's The Tabla of Lucknow (1988) quotes the writer Susheela Mishra as saying that musicians of the then-new generation were “very polished people”. “Originally, musicians could talk about nothing but their own subject . . . Shiv Kumar Sharma is an M.A., and so are many others. They are all graduates, whether they make use of their degrees or not. For example, this Malika Sarabai, who’s coming [to Lucknow soon], she’s a dancer essentially, but she’s got a degree in management. And she’s a philosophy doctorate!”

These “polished people” gave music a new idiom and presentation, ridding it of disreputable associations and training focus on their talent and ability.

Along with musicians in general, the tabla made its own journey.

Tabla players for long did not get the respect of the “lead artiste.” Even Hussian says in his biography that in his early days, “...we tabla players were asked to travel by train whilst the main artists would travel by air.”

However, things started changing with greats like Ustad Alla Rakha, Pandit Samta Prasad, Pandit Kishan Maharaj, and of course Hussain himself.

Pandit Swapan Chaudhury says, “The tabla has been enjoyed as a solo act for centuries. On the global stage too, as awareness about Indian music has increased, the tabla is in great demand.”

However, the change has not been uniform. Outside the esoteric world of concert halls, tabla players are still seen as one part of a performing toli. But this is not always a handicap. Jainendra Dost, who runs the Bhikhari Thakur Repertory Training & Research Centre in Bihar's Chhapra, says, “For folk performances, a tabla player is paid slightly less than say a singer or a harmonium player. However, a tabla player is also likely to be busier, finding work in all kinds of performances. A 'lead artiste' will naturally get fewer opportunities in a year.”

Back to the future

If all the gharanas were created over a century ago, how exactly did Hussain make the tabla relevant? The answer is sheer versatility. The new generation of big, classically trained tabla players are innovating and collaborating with musicians across cultures. Hussain was a member of a fusion band named Shakti, which won the Grammy Award last year.

Others, like Anuradha Pal have tried to “demystify classical music”.

Anuradha Pal

Anuradha Pal

“Over decades, I’ve explored storytelling on the tabla, developing techniques to make it a better melodic-percussive experience. This journey birthed ‘Shiva Shakti on Tabla’ in 2004, ‘Krishna Ke Taal’ with folk musicians in 2014 and ‘Ramayan on Tabla’ in 2023, where the epics are narrated on the tabla,” she says.

Swapan Chaudhury says not just the content, but the presentation has also evolved. “Performers today are more focused on how they dress and how they are perceived by the audiences. Apart from live performances, the tabla is increasingly being used by bands in the West and even in Hollywood.”

The gender divide

The tabla has evolved in other ways too. For the longest time, tabla was dominated by men. One reason for this was the ustaad-shargid system, a largely male world. Once music came to colleges, more girls could join in.

Another reason, says tabla teacher Pandey, is that playing the tabla takes a lot of stamina, and many parents prefer their daughters to take up “easier” art forms. Stuti Raj Verma, who did her masters in tabla from Delhi University and now works for the Bihar government in Motihari, says, “Making music from animal skin takes strength and stamina. My family was interested in music, so my sister and I both learnt the tabla from when we were three. But for that, our diet included a lot of nuts, milk, etc. to keep us strong. Our fingers would often get hurt.”

Anuradha Pal points out another reason. “As an accompanist, you have to travel in mixed-gender groups, where you don't have a say on who travels with you and how. This makes a lot of parents and even performers anxious. Also, to succeed in this field as a woman, you have to work doubly hard to prove yourself, to be taken seriously.”