Stories from a sea bridge

For those on Tamil Nadu’s Rameswaram island, the 110-year-old Pamban railway bridge is a lifeline, a thread binding its people to the mainland and to each other

By Arun Janardhanan

ON THE edge of Rameswaram island, where land ends and the sea begins, three bridges stretch across the blue. The oldest of the three, a rail bridge in the middle, crouches low — steel bones weathered by salt and time. It lies wedged between a busy road bridge and a new, taller railway bridge, its lift span gleaming under the sun.

At her house that’s barely 300 metres away, Ibraahimmal leans against the blue wooden frame of her porch. Born in 1959, in a bungalow once owned by the British, the 66-year-old, her voice calm, but memory sharp, says, “My father was a pilot. Not the one who flies planes — though he liked to say that he could do that too — but a sea pilot. He brought the ships in.”

Her father, M S Sikkandhar, worked at the Pamban port office that once stood between the land and the tides. When the ships appeared on the horizon, they would anchor just off the coast and send a request to the port. The port would alert the railway office at Pamban on the island. The message would reach Madurai, about 160 km away — by telegram or telephone. After he got the all-clear, Sikkandhar would climb into a small boat and row towards the ship. He would then board the ship and the railway bridge would open – its span splicing into two as if in a glorious gun-salute to the passing ship. The captain would hand over control and from there, Sikkandhar would take charge, crossing the old railway bridge and steering the ship towards the Pamban harbour.

The sea between Mandapam in the mainland and Rameswaram is usually calm. Its currents shift with the moon, its winds change without warning, and its “salt eats through steel like termites in wood”, as Ibraahimmal recalls Sikkandhar telling her. It was India’s first sea bridge, and for over a century, the only route for pilgrims and goods until the road bridge, that runs parallel, was added in 1988.

Inaugurated in 1914 under British rule, the bridge stretched 2.06 km across the Palk Strait and had a manually operated double-leaf bascule span that lifted to allow ships to pass. It stayed that way for over a century, surviving a deadly cyclone and decades of corrosive sea winds before it was closed in December 2022, after cracks were found on the structure.

The bridge through which Sikkandhar sailed his ships now makes way for a new railway bridge – India’s first vertical lift sea bridge – that Prime Minister Narendra Modi is set to inaugurate in Rameswaram on Sunday, April 6.

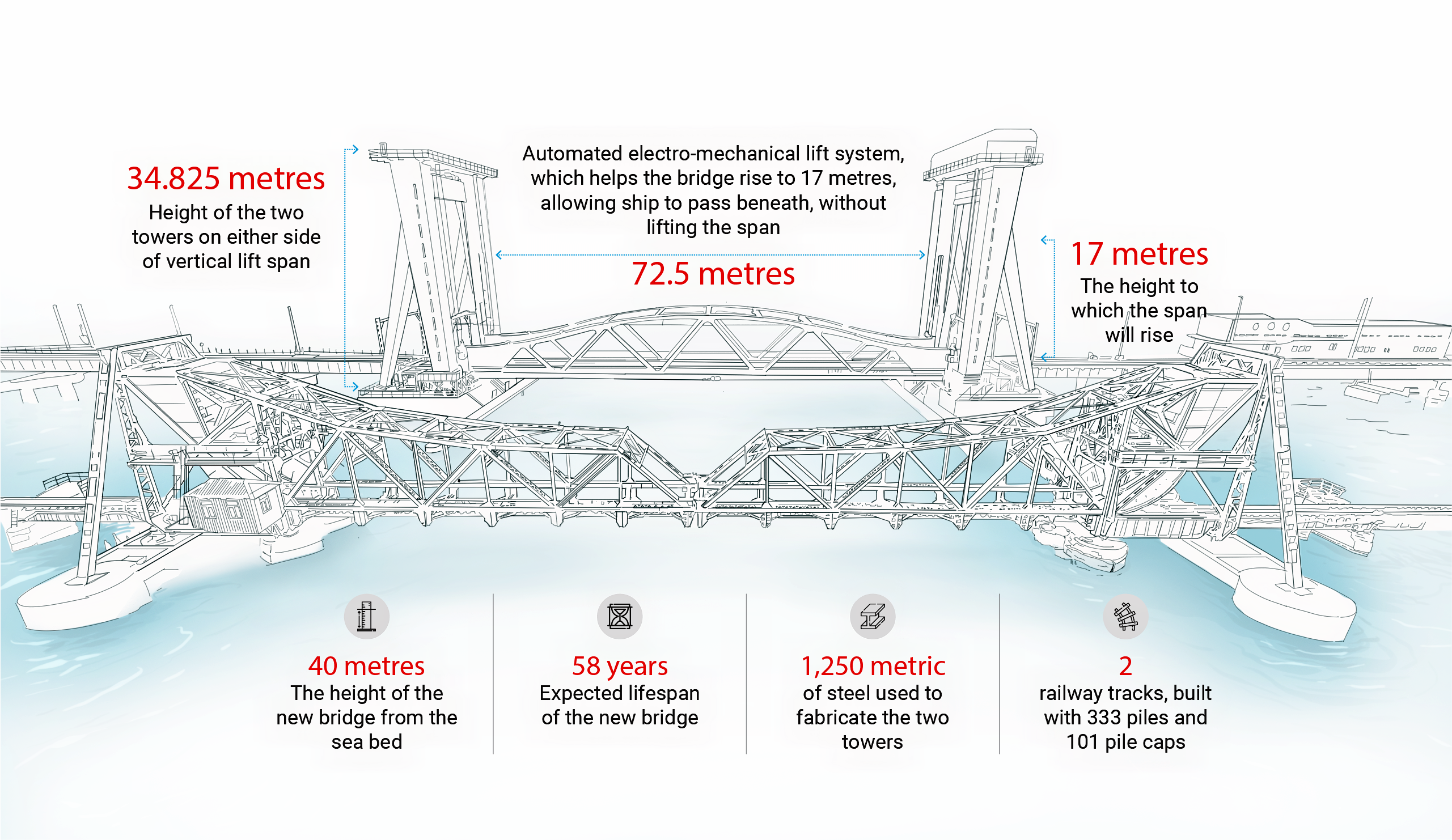

Spanning 2.07 km across the Palk Strait and running parallel to the old railway bridge and the road bridge, the new steel structure features 100 spans, the main one 72.5 m long and equipped with a navigational lift. So now, instead of the spans opening up, it will now rise high above the sea, enabling large ships to pass.

The new bridge, built of steel and reinforced cement concrete by the Rail Vikas Nigam Limited (RVNL) at a cost of Rs 535 crore, stands three meters taller than the 110-year-old Pamban Cantilever Bridge and is automated, with electro-mechanical controls linked to train signals. This modern engineering feat restores rail connectivity to the temple island of Rameswaram, replacing a historic link corroded by time and salt.

“It is the same sea but the tools have changed. This time, machines will do the lifting, not hydraulic levers. Not with muscle and levers, but with circuits and code. But the bridge will carry the same weight — pilgrims, workers, and memories,” said a senior railway engineer at the site, busy with preparations ahead of PM Modi’s visit.

A cyclone and other stories

Rameswaram draws millions of Hindu pilgrims every year to the Ramanathaswamy Temple, one of the Char Dham shrines. It’s here that Lord Rama is believed to have built a bridge, the Ram Setu, to Lanka to rescue Sita. Rameswaram is home to just under 45,000 people as per the last Census. While the Hindus are in majority in the temple town, they live with the Christians and Muslims in harmony and routine familiarity.

Days ahead of PM Modi’s visit, the island is busy slipping into a security cover. Streets are scanned by watchful eyes as the town braces for the inauguration.

With the new bridge, the trains will no longer pass through the old one, but the memories remain — etched in the cables, remembered in tide charts, and passed down like family names.

The cyclone of 1964 comes up in many of these stories. That year, as the rain and winds flattened Dhanushkodi, on the southeastern tip of the Pamban island, it snapped palm trees and snatched a train full of passengers from the railway line. The storm also left the old bridge twisted under its force. But in 46 days, the bridge stood again — stitched back by a team headed by a man who knew steel and will, ‘Metro Man’ E Sreedharan, then a young 32-year-old executive engineer with the civil engineering department of the Railways.

Recalling one of the most important assignments of his career, Sreedharan says, “Of the 146 spans of the bridge, 126 had been washed away, along with two piers. The Railway Board estimated a six-month restoration period and sanctioned Rs 24 crore for the project. They planned to source materials from various locations, including Assam, and manufacture the rest. Given my background in marine engineering, I believed the steel girders might have survived the cyclone. We organised a search and discovered many girders submerged within one to two km of the site. To retrieve them, we improvised by creating floating cranes, as the railway possessed only one steam crane at the time. We then established a local facility to refurbish the salvaged girders and laid prefabricated rails, enabling us to prepare the track within 15 minutes after placing each girder. We finally restored the bridge in just 46 days, significantly ahead of the projected timeline.”

Almost all of Ibraahimmal’s stories feature her “Vappa (father)” and how he navigated ships through the old bridge. “He knew every dip and rise in the channel. He chose the right tide, always at noon, to steer the ships under the bridge. The water levels were good at night too, but too dark to operate a ship. Risky… unless there was a pressing reason such as high traffic or something,” she says. Sometimes, she remembers, ships would wait for days just for her father’s clearance.

In 1964, after the cyclone, as the last British officers packed their bags and headed to the hills of Ooty, they invited Sikkandhar to go with them. He refused. “He said no. He had us. And India.”

Until 1967, the family continued to live in the British bungalow near the sea. The officers sent fruit baskets and letters from their Ooty estate.

Ibraahimmal, who lives metres away from the bridge, has stories of how her father steered ships across the old Pamban bridge. Photos: Arun Janardhanan

Ibraahimmal, who lives metres away from the bridge, has stories of how her father steered ships across the old Pamban bridge. Photos: Arun Janardhanan

Sikkandhar would translate and read them aloud to his wife and children. He would write replies in Tamil, which a stationmaster would help translate into English. “We grew up with their money,” Ibraahimmal says. “That’s what Vappa always said.”

Her husband, Muhammad Meerasa, grins. “She tells me that whenever we fight. She says, ‘Look at my legacy, and look at my fate now.’”

Meerasa has his own legacy. He worked as the lift operator on the old bridge — the one with the manually operated double-leaf bascule span at its heart. He was one of the 16 men — eight on each side of the bridge — who, when a ship approached, would grip long levers and crank the span open. “It took all those men to lift both sides of the span. One held the brake, others rotated a giant lever in unison. Raising the bridge took nearly an hour. Lowering it was more dangerous, though faster,” he recalls.

“I was the bridge inspector too,” he adds. “When I wanted to retire, I passed the job to my son.”

Metres away from Ibraahimmal and Meerasa’s house is Allappiccha’s. By noon, Allappiccha, in his 40s, is on his way back home after work. One of the lift operators on the old bridge, these days, Allappiccha dutifully reports for work though the trains stopped after 2022 and the bridge hasn’t opened since then.

He was 20 when he joined the railways. His first job was as a track checker — tough, thankless work that demanded silence, sharp eyes, and steady feet. One wrong reading could mean a disaster. Every day, he would walk along the tracks with a hammer in his hand and a notebook by his side.

His dad also did the same job. The whole of Pamban knows the story of how his father died a day before retirement, leaving behind not a pension, but a job. So Allappiccha put on the uniform, picked up the register, and went to work. “People inherit land; he inherited a bridge,” says one of his friends who works in the Southern Railway.

The friend also recalls that Allappiccha couldn’t read or write when he first joined -- but now, he “just knows it all”. “He created his own digits – signs for every digit – until his children taught him. They would write the alphabet and numbers for him every night, until he could read the register and log the digits himself,” the friend says.

After years of being a track checker, Allappiccha moved to the Bridge and Rail Infrastructure wing and began operating the lift at the old Pamban bridge. What began as a job of muscle slowly became one of precision. “To lift a bridge and watch a track, you need not just strength but you need to know what the numbers are trying to say with every passing train,” he says.

But it is a job that is set to end forever. “It took about 20 minutes to operate the hydraulic bridge. The new one takes only five minutes to go up,” says Allappiccha, a man of few words who replies with a meditative smile to most questions. At other times, he keeps walking without a reply.

The bridge has 99 spans of 18.3 metres each, with a 72.5 metres vertical lift span at its centre that can be raised up to 17 metres in 5 minutes, 30 seconds.

Built with stainless steel reinforcements and polysiloxane paint, the bridge is designed to withstand harsh marine conditions

The many train journeys

For those on Rameswaram island, the train is more than a mode of transport — it is a lifeline, a thread binding its people to the mainland and to each other. There was a time when nearly everything, from water to essential goods, went back and forth on the railway tracks.

Raj Kapoor, a resident who lives near the Pamban bridge, talks about the half-a-dozen trains that crossed the bridge until 2022. “The passenger trains were a constant presence, several times a day. There was the water tank train, bringing water from the mainland to Rameswaram. The Pallikkoodath Vandi, or school train, ferried children to their schools on the mainland. The train was called that since the laughter of children echoed through the compartments,” says Kapoor.

For the islanders, the trains were arteries of survival, playing a crucial role in local trade. For instance, the Thangachi Madam near Pamban sent out Madurai Malli, the most fragrant of jasmine flowers, that traveled all the way to Madurai and from there to north India. Curry leaves and dried fish found their way to Chennai and distant markets. For fishermen, too, the trains were the most economical way to transport their catch to Chennai. “The train was not just cheap but part of our lives – it is like either we use them or we work in the railways,” he says.

The train was also India’s link to Colombo and beyond. In his 2014 interview with The Indian Express, Captain Hariharan Balakrishnan, a veteran sailor, had recalled his journey in 1959 from Madras to Colombo via Dhanushkodi. “The Boat Mail Express took us from Madras-Egmore to Dhanushkodi. After minimal customs clearances at Dhanushkodi, we boarded a coal-burning steam ferry to Talaimannar in Sri Lanka,” he said. From there, the Colombo Mail Express carried them onward.

Then there’s Baala, the hero of one of the most popular stories that’s told in Pamban. “In the 1970s, Baala from Madurai earned his living by standing in long queues at the US consulate in Chennai for others who came for US visas. One day, Baala had a task -- deliver a passport to a passenger waiting at Dhanushkodi coast for his journey to Sri Lanka and onward to the US. But amidst heavy winds, the trains were halted before the Pamban bridge. He dared to cross the railway bridge on foot, crawling in the heavy rains and wind and clinging on to the bridge for his dear life. Baala finally managed to get to Rameswaram on the other side before delivering the passport on time at Dhanushkodi. He was rewarded by his client who was flying to the US. It’s the same Baala who went on to become the owner of the famous Madurai Travels,” says Kapoor.

The bridge carries painful memories too. During the Sri Lankan civil war, as refugees poured onto Tamil Nadu’s shores, the Mandapam camps in Rameswaram were filled with fear and silence. The town became a theatre of shadow games, swarming with undercover agents who blended into tea stalls and the local markets.

But the deepest of scars are from the 1964 cyclone. For a week, heavy rain had battered the island. At 11.55 pm on December 22, 1964, Train No. 653 — the Pamban-Dhanushkodi Passenger — pulled out of Pamban station on what would be its final journey. On board were 110 passengers and five railway staff. A massive storm with winds touching 280 km/h crossed Sri Lanka and surged toward Pamban. Nearing Dhanushkodi station, a colossal wave struck, swallowing the train and everyone on board.

Over 200 residents of Dhanushkodi also perished as homes were ripped apart and the town drowned. It was the night the wind didn’t sleep. Cut off from the world, it took over 48 hours for rail officials to grasp the scale of the tragedy. Survivors waited more than a week before being rescued. The Pamban bridge lay broken. The government later declared Dhanushkodi unfit for habitation — it stays that way, a ghost town that attracts thousands of tourists every year.

Ibraahimmal, too, has a story of the cyclone, one she has heard from her father – of two bridge operators, Yunus and a Malayali whose name she doesn’t remember, who were on duty at the Pamban railway bridge that fateful night. “When the cyclone hit, they had to cling to the bridge since many steel girders had collapsed into the sea around them. Tying themselves with iron ropes to avoid being swept away by the raging waters, they waited until rescue boats arrived at dawn,” she says. In the story is a mention of how her father witnessed the iconic Tamil actors Sivaji Ganesan and Savitri at Rameswaram a day after the cyclone. “After a visit to the temple, they were stranded in Rameswaram at night and struggled to return to Chennai amid all the chaos,” she says.

In each of these stories is an ode to the train and their own personal journeys.

Peter Bernard, a 52-year-old fisherman from Thangachimadam, takes a pause from drying his net under the road bridge. Watching the sea beyond the new bridge, he says, “If the train moves, we move.”