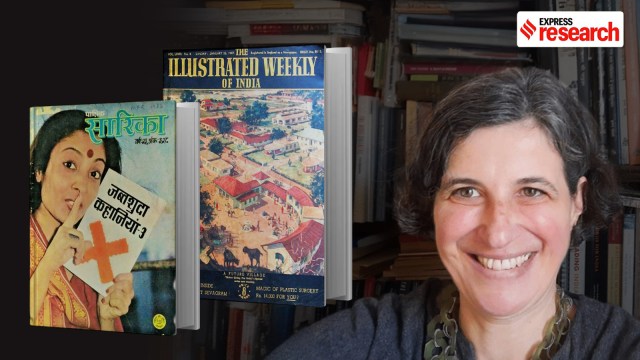

In addition to Kahani, Orsini focuses on Nai Kahaniyan and Sarika, as well as on Hindi writer and editor Kamleshwar (1932–2007), who began his career as a writer and translator of Kahani in the 1950s before going on to edit Nai Kahaniyan and later Sarika between the mid-1960s and the late 1970s.

Story continues below this ad

Magazines in Hindi literary lore

Magazines, Orsini notes in the 2022 book, The Form of Ideology and the Ideology of Form: Cold War, Decolonization and Third World Print Cultures, have occupied a prominent place in Hindi literary history.

In the early 20th century, Hindi magazines were bulky publications, often exceeding 100 pages, that engaged with political, social and literary themes. By contrast, from the 1950s to the 1970s, Hindi magazines in India encompassed a broad spectrum, ranging from small literary imprints and medium-sized enterprises to political reviews and commercial periodicals. “Hindi magazine circulation ranged between 15,000 to 100,000, many times higher than the print run of any new literary book,” Orsini observes.

One reason for this surge in popularity was that magazines had evolved beyond mere publications into spaces of activism—venues for showcasing contemporary writing from other Indian languages as well as a wide range of international literature. With regard to the former, Orsini notes, this constituted a clear nation-building effort.

“[Magazines] were the arena in which critical debates about aesthetics and ideology were fought, and the main platform on which contemporary Hindi poets and fiction writers presented their new work and found readers and recognition,” she writes.

Story continues below this ad

The backdrop of the Cold War

There is no doubt that the magazines’ choice of foreign stories for translation was shaped by Cold War political affiliations. This is seen in the frequent appearance of Chinese, Eastern European, and Russian works in 1950s ‘progressive’ Hindi magazines, while others opted to feature European and American writers instead.

Interestingly, while India under Jawaharlal Nehru was politically non-aligned in the 1950s and 1960s, Hindi magazines were not strictly non-aligned in their literary choices.

By the mid-1960s and early 1970s, the earlier polarisation between the Western and Eastern blocs gave way to a growing literary engagement with the Third World. Magazines like Nai Kahaniyan and Sarika shifted their focus toward Latin American, African, and Asian literatures, lending them unprecedented visibility.

Many authors now regarded as foundational to Latin American, African, and postcolonial literatures—from Horacio Quiroga and Mario Benedetti to Juan Rulfo, José Donoso, and Gabriel Garcia Marquez, from Chinua Achebe and Ngugi Wa Thiong’o to Cyprian Ekwensi and Alex La Guma, among many others—were translated and read in Hindi mainstream magazines like Sarika as early as the 1960s and 1970s.

Story continues below this ad

“As a result, Hindi readers and editors appear to us strikingly less parochial and much more internationalist than we may surmise when we think of Hindi as a ‘regional’ language or bhasha,” Orsini writes.

Reimagining Third-Worldism

Hindi editors like Kamleshwar reimagined Third-Worldism as a “third way” between the two Cold War literary fronts. In the January 1973 special issue of Sarika, devoted to the ‘Third World: ordinary people and writers as fellow travellers’, Kamleshwar framed the Third World not as a geopolitical bloc but as a shared postcolonial condition of underdevelopment after centuries of colonial exploitation.

He said, as cited by Orsini, “From a political viewpoint, the ‘Third World’ is the grouping of geographical units that have gathered on a single platform and accepted that name. But if we move away from that viewpoint and look and connect ourselves to the ordinary people [jan-sāmānya] dwelling in those different parts of the world we shall see that most of the Third World lives in Africa, Latin America and Southeast Asia. In a way, the southern part of the globe is the Third World…”.

“Yet, as we shall see, despite this Marxist analytical language, Kamleshwar’s choice of stories and his aesthetic credo moved resolutely away from an alignment with Leftist internationalism,” Orsini notes. Rather, as he put it, the literature of the Third World was “the voice of the fate of living midstream, tired of both shores.”

Story continues below this ad

That this ‘new world’ was the decolonising world is evident from Kamleshwar’s editorials. Yet, rather than choosing between the two blocs, these magazines drew from both and beyond. The January 1969 issue of Sarika, for instance, featured stories by American writer Henry Slesar, Russian author Viktor Kuteysky and North Vietnam’s Nguyen Vien Thong, alongside works by German writer Heinrich Böll, French author Alain Robbe-Grillet, Indonesian writer Mochtar Lubis, and Iranian author Mohammad Hejazi, among others.

“This literary Third-Worldism, if we call it that,” notes Orsini, “was different and more aesthetically eclectic than the idea of progressive literature in Hindi. It spoke rather to a reorientation away from the Western and Eastern blocs and a curiosity to discover what literatures lay behind the term Third World.”

Interestingly, Orsini finds that Hindi and English magazines from this period reveal a smaller cultural and class distance between them, “certainly compared to the situation today in which the two literary fields appear as quite separate, and very hierarchical, worlds”.

Translations and literary references in Hindi magazines reveal that many Hindi readers read widely in English as well. At the same time, English magazines like the Illustrated Weekly and Quest regularly featured contemporary writing in Hindi and other regional languages.