Written by Iqbal Abhimanyu

“Navratra ho sahi, MP me non-veg nahi!” (For Navratri/Durga Puja to be observed correctly, no non-veg in MP) proclaims the big text in the background as the anchor of a major national Hindi news channel claims that “purity” is very important during the festival, and one is not allowed to eat even garlic and onion. As it turns out, the official bans have been notified for two towns: Maihar in eastern Madhya Pradesh, which houses the famous Sharda Devi temple, and Umaria, another district headquarters in the region.

Whether the prohibition — in effect till October 2 — will be enforced in the rest of the state or other cities is yet to be seen. However, if the recent past is anything to go by, local authorities have increasingly clamped down on the sale of meat, fish and eggs during Hindu or Jain festivals. In August, Indore’s BJP-led municipal corporation had announced a ban on selling meat during Ganesh Chaturthi (August 27), Dol Gyaras (September 3), Anant Chaturdashi (September 6) and the Jain festival of Paryushan. In similar orders in March, Indore and Bhopal had both ordered the closure of such establishments within municipal limits on Gudi Padwa and Chaiti Chand (March 30), Ram Navami (April 6), Mahavir Jayanti (April 10), and Buddha Purnima (May 12).

While this is a familiar script by now in many parts of the country, eating meat, fish or eggs — all of them are facing repeated restrictions during festivals and in spaces considered sacred — has traditionally never been determined by religious identity in MP. Urban and influential sections of the state’s diverse population indeed frown upon the consumption of meat in public, especially in Western MP, which shares borders with Gujarat and Rajasthan and has a strong Vaishnavite influence. However, in a state where Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes consist of 21.1 and 15.6 per cent of the population respectively, any attempt to restrict people’s access to meat is bound to be futile.

I grew up in Hoshangabad, now Narmadapuram, which had mixed Adivasi (ST), Dalit, OBC and “upper-caste” populations. Here, it was common (but unutterable) knowledge that the upper-caste boys would sneak out after dusk or go beyond the village limits to taste the “forbidden stuff,” often clubbed together with a beer or country liquor. In fact, the community most strict in its observance of vegetarianism was the Yadavs, even more so than the few Brahmin families. On the other hand, for the Adivasis, the religious rituals themselves included animal sacrifice. In the early 2000s, for the first time, we saw eggs disappear from shop shelves during Navratri, even though those who wanted continued to consume home-grown meat and eggs during this period.

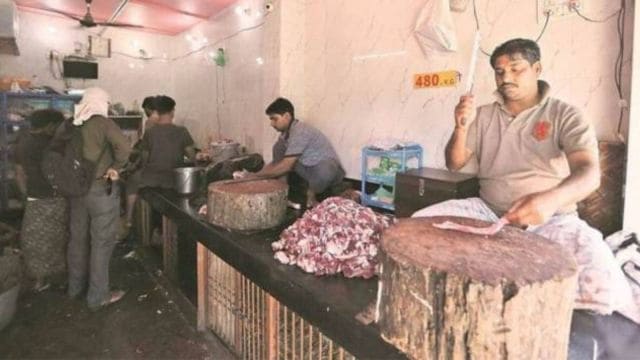

In the cities, the rise of a middle class with money to spend on eating out has meant that the religious or traditional barriers to meat consumption have only weakened, with fast-food joints mushrooming inside the cities and highway dhabas serving chicken and other meats. In this case, the term “municipal limit” assumes great significance. Attempts to ban meat, fish and alcohol in cities considered major religious centres, such as Ujjain, Maheshwar and Narmadapuram, have shifted the sale outside the official municipal limits. Fishermen communities such as Dhimar and Majhi have resisted these efforts, along with others involved in the trade, while their clients come from all castes and classes. Unlike in certain areas in the North, the meat trade in MP is not limited to Muslims in most of the cities.

So, who do these frequent bans serve, and how effective are they? The development can be linked to the rise of the Hindu right-wing in both the state’s politics and discourse. Former Chief Minister Uma Bharti, who brought the BJP back to power in the state in 2003 after a hiatus of 10 years, was one of the first leaders to demand a ban on alcohol and meat consumption in religious cities. Similar attempts to enforce these bans in religious centres were also made during the Shivraj Singh Chouhan administration that lasted over a decade, but were never entirely successful.

Current CM Mohan Yadav had signalled a shift when he announced curbs on the sale of meat and eggs in open spaces hours after taking oath in December 2023. Subsequently, major cities such as Indore and Bhopal have also sought to curb the sale of these products under the pretext of protecting religious sentiments and sanctity. Earlier this year, the CM announced a ban on the sale of liquor in 19 “religious towns”, which include nagar palikas and nagar panchayats. However, in Ujjain, this has again simply meant the mushrooming of liquor shops just outside the municipal limits, where the high footfall is visible on most days.

On the other hand, meat continues to be served in multinational food retail outlets as well as upscale restaurants across cities. Earlier this year, during the Chaitra Navratri in March-April, when the Indore municipal corporation had banned the sale of meat in the city, a Congress leader had questioned why chains like KFC and McDonald’s remain exempt.

However, this argument is counterproductive, as the state has no dearth of vocal and radical right-wing groups that would be eager to extend the ban to all establishments.

In its more aggressive avatar since 2023, the BJP-led state government has sought to weaponise differences in eating habits and religious rituals as part of its polarising rhetoric against minorities. However, the state’s diversity and the dynamics of social mobility act as a bulwark against this discourse. The majority of the state’s population — not just Muslims — now has to choose between defending its eating habits or capitulating to a majoritarian notion of Hinduism that seeks to impose an artificial uniformity on all believers.

The writer teaches at Delhi Skill and Entrepreneurship University