Recent events pertaining to pro-Khalistan activists in Western countries once again bring into focus the diabolical role of some overseas Indian groups working in tandem with various anti-India elements. This is a manageable challenge for the Indian State, even when caught on the wrong foot. One must, however, distinguish between the threat posed by such anti-India elements and the challenge posed by the growing political activism of overseas Indians, both in host and home countries. The latter draws attention to the complex nature of the political relationship between India and its worldwide diaspora.

The growing political engagement of overseas Indians in host and home country politics has become a challenge for Indian diplomacy. Political elements in the Indian diaspora critical of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s politics are one side of the same coin that the Bharatiya Janata Party tries to encash through overseas Indians. Drawing the diaspora into both diplomacy and domestic politics can cut both ways.

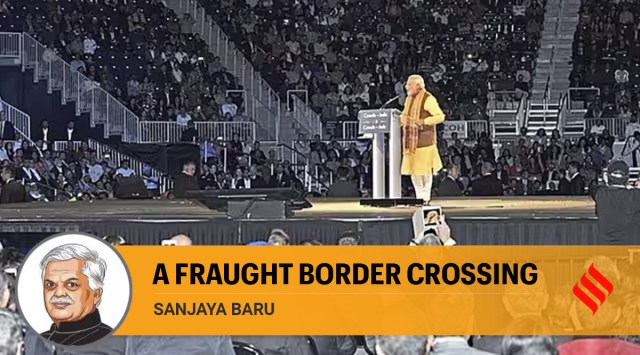

By mobilising overseas Indians every time Prime Minister Modi travels abroad, encouraging them to cheer “Modi! Modi! Modi!”, and drawing them into domestic political campaigning in India, the BJP has helped politicise the diaspora. So, if in London, New York, Houston and across the world pro-Modi groups are shown on Indian television, those politically opposed to his leadership also seek media visibility. The PM’s highly personalised style of diplomacy and its use in domestic politics has blurred the distinction between the diaspora’s loyalty to the motherland and support for an individual politician.

The ruling dispensation in New Delhi would know that it, in fact, took the first step in the political mobilisation of the diaspora. If the BJP ensured publicity at home for pro-Modi groups overseas, others have sought publicity for not just anti-Modi groups but also anti-India elements. Sections of the Indian media have played along with the BJP and interpret every criticism of the PM as criticism of the country. This trend has created great concern in countries that host the Indian diaspora. Many of them have begun to keep a close watch on political activists among overseas Indians for fear that Indian political rivalries could spill into their own domestic politics or derail diplomatic relations.

Interestingly, the leadership of the Indian national movement was fully alive to the political challenge that free India could face from the political activism of the diaspora. After all, in 1947, anti-colonial movements were spreading across the British Empire and other European colonies, inspired by India’s example and achievement. In most British colonies, overseas Indians were active in such movements. What relationship should India, the mother country, maintain with its diaspora under such circumstances? This question exercised the minds of the national leadership.

In an essay on ‘India and Its Diaspora’ (Indian Foreign Affairs Journal, Oct-Dec 2006), diplomat Niranjan Desai recorded three strands of thinking within the leadership of the national movement on the potential relationship between overseas Indians and the home country. Persons like the Aga Khan and Sir Pherozeshah Mehta were in favour of India retaining a close relationship with British imperial territories worldwide and using them as destinations for Indians. They hoped that an over-populated India could relieve itself of this burden by continuing to encourage Indians to settle overseas.

A second group, comprising Tej Bahadur Sapru, G A Natesan, V S Srinivasa Sastri and Purshottamdas Thakurdas went a step further. They asserted the rights of migrant populations and demanded equality of status and treatment of overseas Indians along with native populations across the British empire. As subjects of the empire, the group believed, both migrants and natives deserved equal status irrespective of national and ethnic origin. They, therefore, advocated that the government of free India be proactive in securing the rights of overseas Indians in their host countries.

However, Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru disagreed with all of them. Describing theirs as a “humanitarian” view, Desai notes that both Gandhi and Nehru wished that in overseas British territories, Indian communities should eventually merge with the native population and integrate with the host country. They should not retain any “dual loyalty” between home and host country. Nehru would often remind overseas Indians that they should seek to integrate themselves into their host countries, securing for themselves all the rights of citizenship of their host country.

This concern was based on the fact that during the freedom struggle, the Indian National Congress had branches and activists around the world who campaigned for India’s freedom from colonial rule. From V K Krishna Menon to Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose, important political leaders campaigned for India’s freedom from abroad. Nehru was keen that independent India should draw a line between domestic politics and the politics of overseas Indians. He told the Lok Sabha in 1947, “Our interest in them (overseas Indians) becomes cultural and humanitarian and not political.” This view, expressed in the context of British territories, would be relevant today for the entire Indian diaspora. Once overseas Indians become citizens of other countries, they should cease to be involved in the politics of the motherland.

The BJP has, in recent years, taken a different view, increasingly mobilising overseas Indians for political gain at home. In doing so it may have contributed to the politicisation of the diaspora and its greater involvement in Indian politics. By blurring the distinction between religion and politics the BJP has also contributed to the politicisation of what was essentially social and cultural activity of overseas Indians. That this has had an impact on India’s diplomatic relations with nations hosting overseas Indian communities should not have come as a surprise to those well aware of the possibility.

Some diaspora politicians seem to be willing to play along with this. British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak has worshipped cows in England and ensured high visibility to a temple visit in New Delhi ostensibly to woo Hindu votes in England and the friendship of rulers in New Delhi. This mixing of religion and politics, of politics and diplomacy and of the identity of a nation with an individual is a dangerous cocktail that does not serve India’s relations with the world.

The writer was advisor to former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh