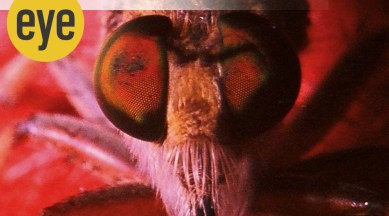

Who’s got the best eyesight in the world?

Can it be an owl who can see at night, or a human being whose vision is seven times sharper than a cat or a dog

At first, it even left Charles Darwin temporarily bemused: How could something as perfectly designed and complex as the living eye, ever have evolved? Creationists led by English philosopher William Paley in 1802 claimed that the eye was yet another example of creative design. Darwin stuck to his guns though and bit by bit, the story of what went on in Mother Nature’s optical workshop over the last 500-600 million years came to light. Today, when we peer through our telescopes or down a microscope, we need to remind ourselves that yet again we are adapting Mother Nature’s technology: we’ve only unraveled what she has done – not originally invented anything.

Apparently, it all began some 500-600 million years ago when the “Cambrian Explosion” began, leading to a burgeoning of different species on Earth. Unicellular organisms existed that had what was called “eyespots”, which had patches of photo-sensitive proteins used for making food through photosynthesis. They could just about make out light from dark and the cells that had eyespots could swim towards or away from a source of light, which was of survival value. Two systems, in the form of proteins worked in tandem: the light-sensitive proteins (called opsins) which changed shape when light hit them, and the ion channels which responded to the change by generating an electrical signal.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

Gradually these organisms evolved to focus their light-sensitive cells in a small depression making it easier to detect the source of light and movement. The depression further evolved into a “pit” which enhanced this capability and the pit became a pinhole, sharpening the focus

further. To protect the opening, a thin layer of skin grew over the opening which evolved into a lens.

As the creatures evolved in other ways, so did eyes, and the sophistication increased. The light sensitive patch at the back of the eye – the retina – developed specialised cells – called rods and cones – the former to detect objects in low light, the latter to detect colours, both linked via the optic nerve to the brain, informing it of what it was seeing. The amount of light allowed in was controlled by muscles around the iris like a diaphragm which contracted or expanded the pupil, which was the actual “pinhole”. The eye was spherical, filled with a clear liquid called the vitreous humour. Further specialisations evolved: the fovea is a special patch at the back of the retina responsible for extra-sharp central vision, useful for us while driving and for raptors while targeting their prey.

In evolutionary terms, scientists conclude that the progress from light-sensitive cells to a perfectly functioning eye would take just 3,64,000 years assuming a 0.005 per cent improvement with every generation, literally just a blink of the eye. At first, it was believed that eyes evolved independently in different animals; there were huge differences in design and ability. Insects had compound eyes comprising thousands of facets or individual lenses, which either formed individual or combined images. Other creatures had simple eyes, with a single lens. We have three colour detecting photoreceptor cells (cones) in our eyes – for red, green and blue, dogs, just two.

But tell-tale genes and the presence of the light sensitive protein molecules – the opsins – which were there right at the beginning indicated that they had all evolved from a common ancient ancestor and then went their own ways depending on what they were required for.

Service and maintenance issues were not neglected either: we have tears to clean our eyes and birds and reptiles have a nictitating membrane which works rather like a windshield wiper – and which also protects the eyes of birds like falcons and gannets, while diving at suicidal speeds. Predators, like the carnivores and raptors, usually have forward facing eyes giving them binocular vision and thus the ability to inpoint their targets accurately, while prey species, like horses and rabbits have eyes on the sides of their faces giving them a wide-angle coverage, to help detect predators sneaking up from behind.

Eagles are thought to have the best eyesight of all; their eyes are as many as eight times sharper than ours. We don’t do too badly either. Our vision is four to seven times as sharp as those of cats and dogs and 100 times sharper than that of a mouse or fruit fly! Owls have a huge number of rods (light-detecting cells) to help them see during their night-hunting expeditions. Perhaps, the most sophisticated eyes belong to the mantis shrimp, which have 12 to 16 photo-receptors and can see both polarised and ultraviolet light. Snails can just make out light and dark, mosquitoes not much more.

It is thought that the rapid evolution of the eye partially contributed to the Cambrian Explosion, suddenly life got moving! Predators could chase after prey, and living creatures could wander long distances and evolve further. It is mind-boggling to think how infinitesimal improvements in each generation, over a million of years, could lead from something quite crude like light-sensitive cells to something as sophisticated (and beautiful) as the eye. We take these great triumphs of nature for granted and can only copy them.

We, and many animals, use our eyes for more than just seeing. The besotted look deep and soulfully into the eyes of their partners, our dogs look pleadingly at us and then the biscuit we aren’t giving them, monkeys glare and challenge all who look straight at them, the mischievous slow-wink at members of the opposite sex (and cause furore in society) and the fixed pitiless golden eyes of the lion leave in no doubt, its intention towards you.