Click here to follow Screen Digital on YouTube and stay updated with the latest from the world of cinema.

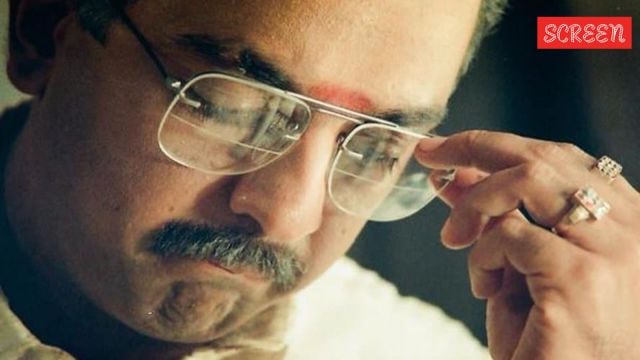

Revisiting Mani Ratnam and Kamal Haasan’s Nayakan, not as a gangster epic, but as an existential melodrama in disguise

Nayakan is not Tamil cinema’s The Godfather or Yash Chopra’s Deewaar. Those comparisons are perfunctory. At its heart, it is an existential quest of a man.

Nayakan is the story of a man who thought he was saving others, only to realise he was trying to save himself from the silence within.

Nayakan is the story of a man who thought he was saving others, only to realise he was trying to save himself from the silence within.Rarely in cinema does a man weep after revenge. When he does, it is often framed as relief, a final letting go. A wound closed, the audience applauds. Justice, they think, has been served. But Nayakan refuses such ease. When Naicker (Kamal Haasan) kills the policeman who murdered his foster father, he does not feel triumph. There is no music to lift him, no silence to dignify the act. Instead, he walks to the policeman’s house. The widow sits in grief. And there, in the wreckage of a family broken by his hand, Naicker sees the child. The child who does not know, cannot know that the man standing before him ended his father’s life. He walks up to Naicker, unaware, and says only this: “My father is dead.” Naicker breaks. He does not cry for the man he killed. He cries for the boy. For the knowledge that vengeance, even when justified, is never clean. That violence does not end with the act; it seeps and spreads. That the blood of the guilty leaves the innocent stained. This moment does not ask for sympathy. It does not moralize. It simply shows that in the world Naicker inhabits, every gain is a loss, every justice a wound, every act of power a compromise.

This moment is the soul of Nayakan. It is where Mani Ratnam’s vision breathes deepest. It is where the film stops looking outwards and turns inwards. For the first time, Naicker begins to question the single belief that carried him through life. As a boy, he is told by his foster father: “Anything that helps others is not wrong.” The line strikes him not as advice, but as truth. No wonder, from that point on, the film moves with an inevitability. The next time we see him, he is grown. He has aged, both in years and in belief. That one sentence has become the axis of his world. Through it, he finds purpose: to stand against the systems that wronged him, to protect the people around him, to rewrite the balance with his own hands. So when he kills the policeman, he does more than avenge his father’s death. He removes a figure of power who brought fear and violence to his community. In that act, Naicker becomes Nayakan — the people’s hero.

Also Read | Why Mani Ratnam’s Nayakan remains a magnificent mob epic

So he becomes the law himself. Not through power alone, but through presence. Through a kind of authority the city cannot name but must obey. He rises up the ladders of survival and influence. Yet he never leaves behind the words that gave him direction. Nor the people he sees himself in, Tamils, scattered at the edges of Bombay, caught in a city that never lets them forget they do not belong. He becomes a don, yes. But also a figure people turn to. A woman with a dying child comes to him, not the state. It is Naicker who brings her to the doctor. It is Naicker who forces care into a system built on neglect. It is Naicker who adopts the very child who made him pause, the son of the man he killed. He ensures the boy and his mother are taken care of, as though by doing so he might contain the fracture within himself, he might redeem himself. But life is not that simplistic. It does not resolve so neatly. He can bend the world outside to his will, but not the one within. That one keeps returning, without warning.

It happens again. His wife is killed in a gangland crossfire. Another cost, another silence. And this time it is his daughter who stands before him. She does not accept the world he has made. She questions it. And in her eyes, he sees again the doubt he thought he had buried. Once again, he breaks. And once again, he has no words. Because heroism, as the film insists, is a distant construction. From afar, it can look clean. Up close, it is compromise, pain, and solitude. It carries a weight the hero cannot set down. It asks more than it gives. Once again, he turns away, not out of indifference, but out of fear. He sends his children away from him. Not only to protect them from the world he inhabits, but to protect himself from seeing who he’s become through their eyes. Perhaps that’s why he never wanted his son to follow him. He wanted the cycle to end with him. He believed he could carry it all alone, that his choices would contain their damage within his own body. But fate is not so obedient. Life does not bend to the logic of sacrifice.

There’s a searing moment in Nayakan where Mani Ratnam pays direct homage to Yash Chopra’s Deewaar.

There’s a searing moment in Nayakan where Mani Ratnam pays direct homage to Yash Chopra’s Deewaar.

It is only fitting that the life he built, the power, the protection, the violence consumes what he most hoped to preserve. His son is lost to the very world Naicker once vowed to fight. His bond with his daughter splinters under the weight of all that has gone unspoken. He believed that by sending her away, he could silence the questions. That distance could shield them both, from each other, from the past. But truth does not wait at the door. It finds its way in. And in the film’s most searing moment, (where Ratnam pays homage to Yash Chopra’s Deewaar), his daughter stands before him, questions him about the kind of life he has lived? About what kind of justice leaves bodies in its wake? Naicker, like Vijay in Deewaar, reaches for justification. He speaks of pain, of oppression, of the choices he had to make. He insists it was for others, for those who had no voice. But, like Ravi, she does not accept this. She sees through the worn narratives. She knows that no amount of suffering gives a man the right to remake justice in his own image. That the cost of such power cannot be passed on to others.

Also Read | Kamal Haasan and Mani Ratnam’s Nayakan is not timeless, nor has it aged well; let that sink in

However, the tragedy of Naicker’s life is that it has already happened. The tragedy is not that he failed, but that he believed he could control where the consequences would land. The story of Nayakan remains suspended between two truths: that he lived by a principle meant to help, and that it slowly consumed him. That he rose for his people, and in doing so, lost his place amongst them. That he tried to end a cycle, and could only delay it. Hero. Don. Father. Fugitive. All of them are real. But none of them are enough. And it’s here that Mani Ratnam reveals what the film has always been. Not a gangster epic. Not a Tamil Godfather. Not a collection of nods to Salim–Javed. All of that is perfunctory. The real story is something else. It is the story of a man’s gradual collapse. A man who believed he was saving others, only to realise too late that all along, he was trying to save himself. From guilt. From doubt. From the unbearable silence within. No wonder the film begins with Naicker as a boy, asking his father what is good and what is bad. No wonder it ends with his grandchild asking him the same question. No wonder the story begins with a child killing a policeman for killing his father. And ends with a policeman’s son killing a gangster for the same reason. No wonder, we call it poetic justice.

Photos

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05