Walk or die: Stephen King’s The Long Walk feels too real now

Stephen King’s first novel imagined a dystopian America that sacrifices its youth for spectacle. Six decades later, as The Long Walk reaches the screen, the nightmare feels closer than ever.

As the film adaptation of The Long Walk hits the big screen nearly 45 years after it was published, the US is in the grip of a new nightmare.

As the film adaptation of The Long Walk hits the big screen nearly 45 years after it was published, the US is in the grip of a new nightmare.Any game looks straight if everyone is being cheated at once.

In 1966-67, when Stephen King was a freshman at the University of Maine, the air was heavy with the stench of death and despair. Young men were being fed into the American war machine and spat out all over the jungles and rice fields of far-away Vietnam, sacrificed for dubious ideals propounded by old men in Washington.

Amidst a widespread sense of betrayal over the lost promise of youth, King wrote a book whose plot revolved around an annual race in an America of the future, in which 100 young men compete for the ultimate prize: Getting whatever they want for the rest of their lives. The catch? For one to win, the other 99 must die.

As the film adaptation of The Long Walk hits the big screen, 45 years after the novel was published in 1979, the US is in the grip of a new nightmare. In the months since Donald Trump took the oath of office for the second time, chaos has reigned, polarisation deepened and political violence spiralled.

The killing this week of conservative political activist Charlie Kirk as he was speaking at an event in Utah Valley University sends yet another chilling signal in a nation where every institution seems to be under siege, with the highest office in the land actively undermining constitutional freedoms, and guns, always troublingly ubiquitous, speaking louder and louder. The American dream is fast giving way to something scary.

The name of the game

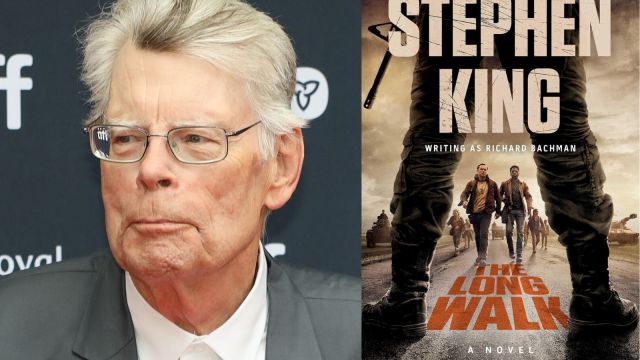

As the first book that King ever wrote , The Long Walk, has a special place in the hearts of his fans. (Source: amazon.in)

As the first book that King ever wrote — although it was published only after Carrie, Salem’s Lot, The Shining and The Stand — The Long Walk has a special place in the hearts of his fans. (It was initially published under the pseudonym Richard Bachman, a strategy to overcome the prevailing publishing shibboleth that authors risked reader fatigue if they released more than one title in a year.)

But The Long Walk’s appeal goes beyond the sentimental and it is routinely listed as a fan favourite because it remains an excellent example of King’s ability to extract horror from the depths of human psychology. Unlike many of the books that came later, especially The Dark Tower series, there is no elaborate world-building here. What little we know about the America in which the titular event takes place emerges from the conversation that the participants have with each other: That it is bleak and poor, that dissent is severely punished, that death is as easy as getting a leg cramp and being unable to finish a race.

Story continues below this adThe plot is straightforward: Young men across the US volunteer to participate in a race, the winner of which can ask for anything he wants. A hundred are selected via lottery to walk on a pre-determined route at a minimum speed of 4 miles per hour (reduced to a more realistic 3 mph in the film) until only one is left. Anyone who slows down, tries to take a break or attempts to leave the race — which, we are told, is broadcast and watched by millions — is warned three times before being shot.

The book begins and ends with the race, following the participants as their early enthusiasm and confidence begins to crack and overwhelming physical and mental exhaustion sets in, followed by despair and collapse.

This minimalist approach to plot succeeds because of King’s talent — obvious even in this early work — for writing characters who are deeply relatable and whose travails quickly start to feel personal. Almost immediately, the reader feels invested in the fortunes of the main character Ray Garraty, as well as the friends that he makes among his fellow racers. These friendships are the beating heart of this bleak book and even though the reader knows right at the outset that all but one of the 100 young men will die before the end, each death, when it occurs, hits hard.

In different hands, it could have gone horribly wrong, reduced to a macabre spectacle, as character after character falls, but King invests each of the young men — and their deaths — with dignity, even as the circumstances get more and more gruesome.

Story continues below this adThere are no real incidents or happenings to speak of, only a deepening sense of hopelessness. But as the reader trudges along with the racers, whose shoes fall apart and feet swell up, who battle the vagaries of the weather and their own deteriorating mental states to keep on walking even when they know they’re doomed, the storytelling remains rich. Garraty’s thoughts spiral as he questions his motivations for entering this race and confronts his mortality. At the same time, as he and his fellow racers push themselves to the limits of their physical and mental being, repressed memories and shameful secrets well up and they see each other’s humanity in a way they wouldn’t have under better, more normal circumstances.

Who wants to be the last man alive?

The best dystopian fiction set in the US has mined uniquely American nightmares. ( source: amazon.in)

The best dystopian fiction set in the US has mined uniquely American nightmares, from the extreme polarisation on reproductive rights (Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale), to the strong strand of anti-intellectualism in mainstream politics (Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451), from the primordial wound of slavery and racial violence (N K Jemisin’s The Fifth Season trilogy) to the prison industrial complex (Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah’s Chain Gang All Stars).

Like later books, such as The Hunger Games by Suzanne Collins, Ready Player One by Ernest Cline and The Maze Runner by James Dashner, The Long Walk draws on the American genius for spinning entertainment out of anything, including — perhaps especially — suffering. In this, it could even be called something of a pioneer. If actual game shows rely on “elimination rounds” to eventually pick a winner, The Long Walk puts a horrifyingly literal spin on it. In typical Kingian fashion, it gets very gory very quickly as bullets shatter skulls and characters are maimed and killed in the most gruesome ways imaginable; one particular death, which involves a character tearing out his own throat, reportedly gave the writer himself many sleepless nights.

But the real reason that The Long Walk continues to appeal is because its core message about the limits of human endurance transcends the times in which the book was written. If once it was a metaphor for how a society sacrifices its young, today it can be read as an allegory about despair in the face of repressive, overwhelming power. America in 2025, with its political and economic chaos and spiralling violence, seems to be on the brink of something terrible — The Long Walk offers a glimpse of the horror that awaits it at the bottom of the abyss.

- 01

- 02

- 03

- 04

- 05

As the first book that King ever wrote , The Long Walk, has a special place in the hearts of his fans. (Source: amazon.in)

As the first book that King ever wrote , The Long Walk, has a special place in the hearts of his fans. (Source: amazon.in) The best dystopian fiction set in the US has mined uniquely American nightmares. ( source: amazon.in)

The best dystopian fiction set in the US has mined uniquely American nightmares. ( source: amazon.in)