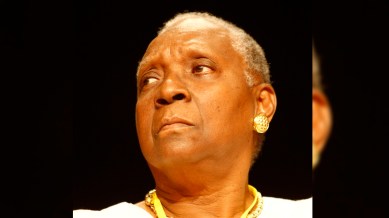

Maryse Condé, ‘Grande Dame of Caribbean Literature’, dies

Adept at novels, essays and plays, Condé influenced many generations of writers through her work on the African diaspora

Twice in her life, upon approaching her mother for encouragement about her writing, Maryse Condé faced opposition. The first time, when she was a teenager, she was accused of inventing a “load of lies” – a painful earful for any budding fictioneer – and the second time, a few years later, in response to her triumphant claim that she would one day write as powerfully as Emily Bronte: “What are you talking about? People like us don’t write!” Conde was confused. “What did (my mother) mean by people like us?” she writes in a 2019 New York Review piece. “Women? Blacks? Inhabitants of small, unimportant islands?”

The exchange “shattered her”, but not forever. Condé, who went on to win the New Academy Prize for Literature, a publicly-voted replacement to the cancelled 2018 Nobel Prize, died Tuesday at the age of 90. She grew up in Guadeloupe, a Caribbean island colonised by the French Kingdom from the 17th to 20th centuries. It hosted enslaved Africans, indentured Native American labour, and suffered lasting unemployment and invisibility on the international stage. Creole, a language “invented in the plantation system as a challenge to the white planters”, was forbidden in schools for much of Condé’s childhood. She travelled to France for studies, eventually taught French literature there, and later gained a scholarship to teach at Columbia University.

Also associated with the political party Union Populaire pour la Libération de la Guadeloupe, Condé has championed the independence of the island from French overseas rule. Her first book, Hérémakhonon (1976) (trans: ‘Waiting for Happiness’), is about a Caribbean woman who goes to a West African country in search of her identity. “… In those days, the entire world was talking of the success of African socialism. I dared to say that the newly-independent African countries were victims of dictators prepared to starve their population,” writes Conde in the 2019 piece. The book sold poorly and fell out of print in six months. “I immediately realized that literature is a dangerous act: never say what you believe to be the truth,” she adds.

But she wasn’t deterred for long. Going on to pen novels like Tituba: Black Witch of Salem (1986), about the Salem witch trials, and Tree of Life (1987), about a Caribbean family’s experiments with marriage and money, she said in a 1999 interview, “I could not write anything… unless it has a certain political significance. I have nothing else to offer that remains important.”

Upon her death, the literary community issued condolences. Writer Nilanjana Roy tweeted, “She was so great, I half believed that Maryse Condé would cheat her trickster friend, Death, and live forever. Grateful for the power of her words.” Writer Alain Mabanckou tweeted, “(Condé) bows out, bequeathing us a work driven by the quest for a humanism based on the ramifications of our identities and the cracks in history. RIP.”