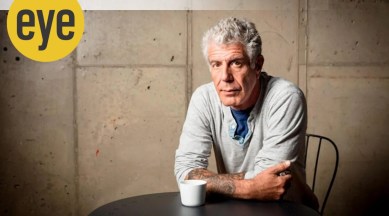

Nobody really knew Anthony Bourdain. And that’s alright

The biography of the late Anthony Bourdain explores the legacy of the popular chef through the narratives of friends and family

Biographies, it is well-known, are not entirely reliable as far as telling the truth is concerned. This has been so right from when the art of the biography started to be recognised as a distinct branch of literature: James Boswell was accused of manipulating quotes to suit his perspective in The Life of Samuel Johnson (1791), while Elizabeth Gaskell was pilloried for trying to scrub away all evidence of her subject’s “immorality” — such as her love for a married man — in The Life of Charlotte Brontë (1857). Trouble with the “truth” — however one might interpret the word — seems to plague all kinds of biographies even today and it could be the same with Bourdain in Stories, the biography of the late Anthony Bourdain.

Laurie Woolever has however sought to evade this genre-specific problem. For, instead of attempting the encyclopaedic approach of most biographers, Woolever has presented the charismatic chef, writer and TV personality through 91 different people — his mother and brother, ex-wives and girlfriends, daughter, former kitchen and TV colleagues, other famous chefs/TV personalities, journalists, employees, friends, publishers and agents.

monthly limit of free stories.

with an Express account.

What emerges is not so much a portrait as a puzzle. Who really was Tony Bourdain — a writer with a burning ambition, a victim of near-crippling imposter syndrome, a celebrity made deeply uncomfortable by his fame, a heroin and crack addict, a hedonist, a mentor, a middling chef, an overgrown child? This complexity is not a bad thing at all, because what Woolever ends up doing is exposing the lie at the heart of any such enterprise: That we can ever, truly, know anyone. In Bourdain’s case, perhaps more so. As a colleague from Bourdain’s time in New York’s kitchens says, “Tony was always playing with how he looked to other people; he was very conscious of it.”

By Laurie Woolever

Bloomsbury

436 pages

Rs 699

This is an especially good approach to take when writing about Bourdain, someone many viewers thought they knew well not just because they had watched him eat and talk his way around the world on critically-acclaimed shows like No Reservations (2005) and Parts Unknown (2013). Television’s Anthony Bourdain was a carefully-crafted persona, designed to make viewers think of him as “Tony”, a louche, wise-cracking but sage figure who, one suspected, would be as interested in their lives as he was in the lives of everyone he met on his shows. His death by suicide in 2018 was mourned globally, even as fans wondered why someone so famous, respected and even loved had taken his own life. The cracks finally showed in the picture.

Woolever, understandably, offers no solution to this particular mystery. Instead, she busies herself with complicating Bourdain’s slickly-marketed public persona, to whose appeal certain, carefully-selected dark episodes — such as his long “bad behaviour” phase as detailed in Kitchen Confidential (2000) — were essential. Despite being his long-time assistant and confidante, Woolever doesn’t insert her own version of Tony into the book. A wise choice, perhaps, considering the wealth of voices the book already contains, as well as the fact that Woolever does, ultimately, get to craft the narrative, deciding whom to interview and whose voice to exclude. The filmmaker Asia Argento, who was his girlfriend at the time of his death and who had a sexual assault allegation against her, is a notable exclusion, although other interviewees talk about the volatile, troubled relationship between her and Bourdain and discuss how this impacted his ties with those around him.

In fact, Woolever’s decision to let her interviewees talk about Bourdain as they saw him, has made for a powerfully moving, riveting read. Everyone has stories (most of which don’t sandpaper the edges) about the man they’re celebrating, whether about the time (pre-worldwide fame) he almost worked for Robert De Niro’s film company in a movie about a corrupt cop or when he practically kidnapped the cat belonging to his second wife (then girlfriend) Ottavia Busia-Bourdain so that she would spend more time with him. But what the book really turns out to be is a memorial or a wake which everyone who knew him — including his readers and fans — would have wished to join in.